An analysis of the “relatio post disceptationem”, Cardinal Erdő’s summary of what was discussed in the first week of the Extraordinary Synod on the Family. The focus was on families facing difficult situations and the Church’s willingness to recognize the positive elements of “imperfect forms” of common-law marriages and cohabitation

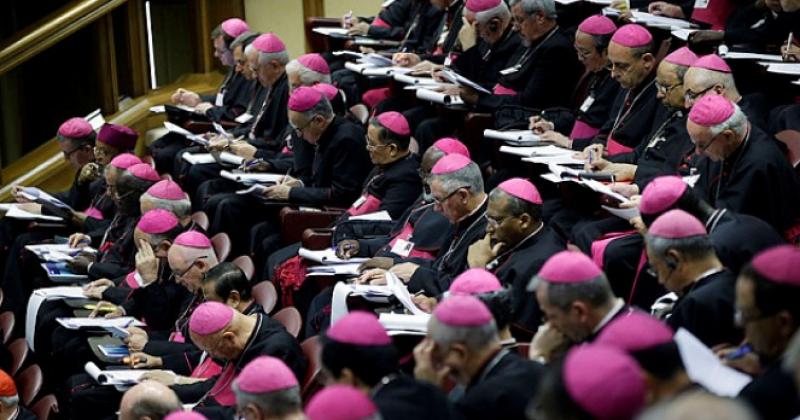

Some interesting aspects emerge in the relatio post disceptationem, the summary of the Synod’s first week of discussions presented this morning by Cardinal Peter Erdő. First of all, it is clear evidence that the daily briefings organised by the Holy See Press Office faithfully echoed what was actually said during the discussions. For example, the Synod Fathers obviously did discuss the problems faced by “wounded” families and families in “irregular situations”. Although this was not the only issue the Synod focused its attention on, it obviously is a key subject, meaning the media did not just make it up. Meanwhile, claims that Cardinal Walter Kasper’s proposal about the possibility of allowing remarried divorcees to take communion under certain conditions was rejected by practically all Synod participants seem to hold no water.

The first thing to point out is the positive outlook and approach that are characterizing the Synod. This echoes the words the young Fr. Battista Montini used in 1929. In a piece for Azione Fucina magazine, Montini wrote that a Christian looks at the world “not as an abyss of perdition but, rather, as a field for the harvest”. “Despite the many signs of crisis in the institution of the family in various contexts of the “global village”, the desire for family remains alive, especially among the young, and is at the root of the Church’s need to proclaim tirelessly and with profound conviction the “Gospel of the family” entrusted to her with the revelation of God’s love in Jesus Christ,” the relatio post disceptationem reads. What is striking is that the Synod Fathers addressed not just the “exasperated individualism” of contemporary culture but also the socio-economic difficulties that often act as an obstacle to marriage or steer a couple towards divorce. They did so adopting a realistic approach.

The relatio post disceptationem is now going to be discussed in the circuli minores, the different language groups the bishops have been split into. Erdő dedicated a significant part of his summary to “gradualness” in “divine paedagogy”. How should the Church accompany those whose marriage has failed? Similarly to what the Second Vatican Council did with other Christian denominations and religions, the relatio mentions the possibility of recognition “positive elements” “even in the imperfect forms that may be found outside this nuptial situation,” such as common-law marriage and cohabitation. Indeed, when common-law marriages “reach a notable level of stability” and are “characterized by deep affection” and responsibility toward offspring, they “may be seen as a germ to be accompanied in development towards the sacrament of marriage.” As far as cohabitation is concerned, the relatio affirms that there is a growing number of cases in which cohabiting couples eventually decide to marry if they receive the right accompaniment and help.

The relatio frequently highlights the inadequacy of a “merely theoretical approach” that is detached from people’s real problems. The role of pastors is not just to read out a set of principles and present doctrinal frameworks from on high, acting as cold messengers who pass on laws and canonical rules. Indeed, the evangelical truth touches the real and often wounded lives of people who have been through all sorts of different kinds of experiences. The Church must be able to make the message of God’s mercy ring out. A God who embraces and loves before he judges. So language is the first element of conversion.

Erdő then affirmed: “What rang out clearly in the Synod was the necessity for courageous pastoral choices. Reconfirming forcefully the fidelity to the Gospel of the family, the Synod Fathers, felt the urgent need for new pastoral paths, that begin with the effective reality of familial fragilities, recognizing that they, more often than not, are more “endured” than freely chosen. But although participants did discuss these choices and the possibility of admitting couples in “irregular” situations to the sacraments, no one defended them as a right or suggested any easy shortcuts. “It is not wise to think of unique solutions or those inspired by a logic of “all or nothing”.” Cardinal Reinhard Marx recently summed up the Synod’s position as such: “Not for everybody nor for anyone”, meaning that possible solutions are to be considered on a case-by-case basis, by looking at each person’s story individually. The Church’s pastors are to achieve this through discernment and by accompanying each individual or couple. “Such discernment is indispensable for the separated and divorced.”

Paragraph number 47 outlines the two positions that emerged during the debate over the administration of the sacraments to remarried divorcees: “Some argued in favour of the present regulations because of their theological foundation, others were in favour of a greater opening on very precise conditions when dealing with situations that cannot be resolved without creating new injustices and suffering. For some, partaking of the sacraments might occur were it preceded by a penitential path – under the responsibility of the diocesan bishop –, and with a clear undertaking in favour of the children. This would not be a general possibility, but the fruit of a discernment applied on a case-by-case basis, according to a law of gradualness, that takes into consideration the distinction between state of sin, state of grace and the attenuating circumstances.” Interestingly, “more than a few Synod Fathers asked themselves the following question: “If spiritual communion is possible, why not allow them to partake in the sacrament?”

The most significant change in terms of approach and language was definitely seen in the part of the relatio that was dedicated to gay people and the Church’s attitude toward them. “Homosexuals have gifts and qualities to offer to the Christian community: are we capable of welcoming these people, guaranteeing to them a fraternal space in our communities?” the text reads. Although the Church remains firm in its refusal to equate same-sex unions to marriage between a man and a woman and to give into pressure – also from international organisations that condition people through funding – to introduce regulations inspired by “gender ideology”, the language used in the relatio is a first: “Without denying the moral problems connected to homosexual unions it has to be noted that there are cases in which mutual aid to the point of sacrifice constitutes a precious support in the life of the partners.”

Finally, it should be noted that despite certain predictions and declarations, Paul VI’s teaching in the Humanae Vitae is still believed to be applicable today and should be re-read, focusing on the need to respect the dignity of a person in the moral evaluation of birth control methods.

There is no doubt then that the frank and free discussions, the “parrhesia” with which the Synod Fathers spoke and the humility with which they listened (as Pope Francis wanted), showed the attention all bishops gave to difficult family situations and also highlighted a number of possible approaches to meet the needs of those who are suffering due to their exclusion from the sacraments. This week discussions continue and at the end the Synod Fathers will vote on the final relatio synodi text which will act as a working document for local Churches ahead of the Ordinary Synod that is due to take place from 4 to 25 October, on the theme “The vocation and mission of the family in the church and the modern world”. This Synod is a long and open journey that is involving Christian communities more than ever before.