‘There is only one true remedy to death, and we Christians are robbing the world if we do not proclaim it by our words and our lives’

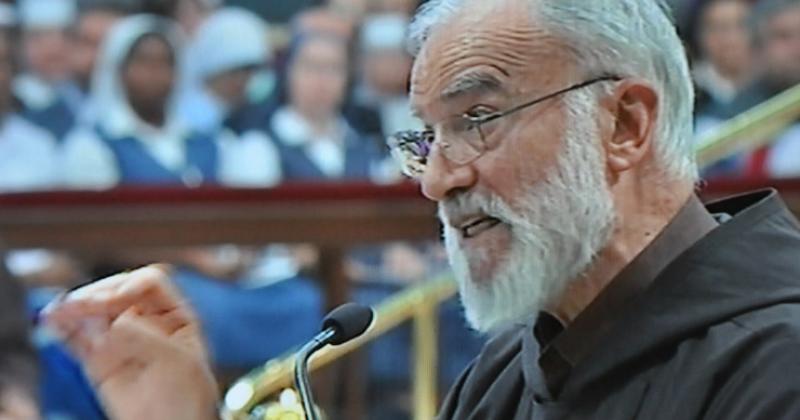

Following is the third Lenten homily 2017 given this year by preacher of the Pontifical Household Capuchin Father Raniero Cantalamessa:

The Holy Spirit in the Paschal Mystery of Christ

In the two preceding meditations we tried to show how the Holy Spirit leads us into the “fullness of truth” about the person of Christ, making him known as “Lord” and as “true God from true God.” In the remaining meditations our attention will shift from the person of Christ to the work of Christ, from his being to his acting. We will try to show how the Holy Spirit illuminates the paschal mystery.

Scarcely had the program for these Lenten sermons been made public when I was asked this question in an interview by L’Osservatore Romano: “How much time will you devote to current affairs in your meditations?” I responded that if “current affairs” referred to contemporary events and situations, I was afraid there would be very little of that in the upcoming Lenten sermons. But, in my opinion, “current” does not just mean “what is going on now,” and it is not a synonym for “recent.” The most “current” things are eternal things, those things that touch people in the most intimate core of their being in every age and in every culture. There is the same kind of distinction between “urgent” and “important.” We are always being tempted to put the urgent ahead of the important and to put the “recent” ahead of the “eternal.” This tendency has been increasing especially because of the rapid pace of communication and the media’s constant need for more news.

What is more important or timely for the believer, and for every man and every woman, than to know if life has meaning or not, if death is the end of everything or, on the contrary, if death is the beginning of real life? The paschal mystery of the death and resurrection of Christ is the only answer to such questions. The difference between this relevant issue and those of the news media is the same as between someone who spends time looking at a design left by a wave on the shore (which the next wave erases!) and someone who lifts his or her gaze to contemplate the sea in its immensity.

With this in mind, let us meditate on the paschal mystery of Christ, beginning with his death on the cross. The Letter to the Hebrews says that Christ “through the eternal Spirit offered himself without blemish to God” (Heb 9:14). The “eternal Spirit” is another way of saying the Holy Spirit, which is confirmed by an ancient variation of the text. This means that Jesus, as man, received from the Holy Spirit dwelling in him the impulse to offer himself in sacrifice to the Father as well as the strength that sustained him during his passion. The liturgy expresses this very conviction when, in the prayer that precedes communion, the priest says, “O Lord Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, Who, by the will of the Father, with the cooperation of the Holy Spirit (cooperante Spiritu Sancto), [You] have by Your death given life to the world. . . .”

The same dynamic that occurred in the sacrifice also occurred in prayer. One day Jesus “rejoiced in the Holy Spirit and said, ‘I thank you, Father, Lord of Heaven and Earth.’” (Lk 10:21). It was the Holy Spirit who made the prayer rise up in him, and it was the Holy Spirit who urged him to offer himself to the Father. The Holy Spirit, who is the eternal gift the Son makes of himself to the Father in eternity, is also the one who urged him to make a sacrificial gift of himself to the Father for our sake in time.

The connection between the Holy Spirit and the death of Jesus is highlighted primarily in the Gospel of John. “As yet the Spirit had not been given,” notes the Evangelist concerning the promise of living water, “because Jesus was not yet glorified” (Jn 7:39), that is—according to the meaning of “glorification” in John—Jesus had not yet been lifted on the cross. Jesus “yielded up his spirit” (Matt 27:50) on the cross, symbolized by the water and the blood; John in fact writes in his First Letter, “There are three witnesses, the Spirit, the water, and the blood” (1 Jn 5:8).

The Holy Spirit brings Jesus to the cross, and from the cross Jesus gives the Holy Spirit. At the moment of his birth and then publicly in his baptism, the Holy Spirit is given to Jesus; at the moment of his death, Jesus gives the Holy Spirit. Peter says to the crowd gathered on the day of Pentecost, “Having received from the Father the promise of the Holy Spirit, he has poured out this which you see and hear” (Acts 2:33). The Fathers of the Church loved to highlight this reciprocity. “The Lord received ointment [myron] on his head,” says St. Ignatius of Antioch, “to breath incorruptibility on the church.”

At this point we need to recall St. Augustine’s observation regarding the nature of the mysteries in Christ. According to him, there is a true celebration of a mystery, and not just of an anniversary, when “the commemoration of the event is so ordered that it is understood to be significant of something [for us] which is to be received with reverence as sacred.” And this is what we would like to do in this meditation, guided by the Holy Spirit: to see what the death of Christ signifies for us, what it changed concerning our death.

One Died for All

The Church’s creed ends with the words, “I look forward to the resurrection of the dead and the life of the world to come.” It does not mention what will precede resurrection and eternal life, that is, death. Rightly so, because death is not the object of faith but of our experience. Death, however, touches all of us too closely to pass over it in silence.

In order to evaluate the change brought by Christ concerning death, let us see what remedies human beings have looked to in order to deal with the problem of death, especially since they are the ones with which people still try to “console themselves” today. Death is the number one human problem. St. Augustine anticipated contemporary philosophy’s reflection on death:

When a child is born there are so many speculations. Perhaps he will be handsome, perhaps ugly; perhaps he will be rich, perhaps poor; perhaps he will grow old, perhaps he will not. But no one says, “Perhaps he will die, perhaps he won’t.” Death is the only absolute certainty in life. When we know that someone has dropsy [this was an incurable disease at that time, but there are others today], we say, “Poor fellow, he is going to die; he is condemned to die; there is no cure.” Should we not say the same about anyone who is born? “Poor fellow, he has to die; there is no cure; he is condemned to die!” What difference does it make if he has a bit longer time or a bit shorter time to live? Death is the fatal disease we contract by being born.

Perhaps better than thinking of our lives as “a mortal life,” we should think of it as “a living death,” a life of dying. This thought by Augustine has been taken up from a secular standpoint by Martin Heidegger who made death, in its own right, a subject for philosophy. Defining life and a human being as a “being-toward-death,” he sees death not as an event that brings life to an end but as the very substance of life, that is, as the way life unfolds. To live is to die. Every instant that we live is something that get consumed, that is subtracted from life and handed over to death. “Living-for-death” means that death is not only the end but also the purpose of life. One is born to die and for nothing else. We come from nothingness and we return to nothingness. Nothingness is then the only option for a human being.

This is the most radical reversal of the Christian vision, which sees a human being instead as a “being-for-eternity.” Nevertheless, the affirmation that philosophy arrived at after its long reflection on human beings is neither scandalous nor absurd. Philosophy is simply doing its job; it shows what human destiny would be like if left to itself. It helps us understand the difference that faith in Christ makes.

More than philosophy, it is perhaps the poets who speak the simplest and truest words of wisdom about death. One of them, Giuseppe Ungaretti, speaking of the frame of mind of the soldiers in the trenches during World War I, described the situation of every human being confronting the mystery of death:

They stand like leaves on the trees in autumn

Scripture itself in the Old Testament does not have a clear answer on death. The Wisdom books speak about it but always from the standpoint of a question rather than of an answer. Job, the Psalms, Ecclesiastes, Sirach, Wisdom—all these books dedicate considerable space to the theme of death. “Teach us to number our days that we may get a heart of wisdom,” one psalm says (Ps. 90:12). Why are we born? Why do we die? Where do we go when we die? These are all questions that are without any answers for the Old Testament sage except this one: God wills it to be so; there will be judgment for everyone.

The Bible refers to the disquieting opinions of unbelievers of that time: “Short and sorrowful is our life, and there is no remedy when a man comes to his end, and no one has been known to return from Hades. . . . We were born by mere chance, and hereafter we shall be as though we had never been” (Wis 2:1-2). Only in this book of Wisdom, which is the latest book of biblical wisdom literature, does death begin to be illuminated by the idea of some kind of recompense after death. The souls of the righteousness, they thought, are in God’s hands, even if they did not know exactly what that meant (see Wis 3:1). It is true that in one of the psalms we read, “Precious in the sight of the LORD is the death of his saints” (Ps 116:15). But we cannot place too much weight on this verse that has been cited so often since its meaning seems to point to something else: God makes people pay dearly for the death of his faithful ones, that is, he is their avenger and holds people to account.

How have human beings reacted to the harsh necessity of death? One dismissive response has been not to think about it and to distract oneself. For Epicurus, for example, death is a non-issue: “So long as we are existent,” he said, “death is not present and whenever it is present we are nonexistent.” Death, therefore, is not really a concern for us. This approach of exorcizing death is also found in the laws of the Napoleonic Code that placed cemeteries outside the city limits.

People also clung to positive remedies. The most universal one is having offspring and continuing to live through one’s descendants. Another was living on through fame: “I shall not wholly die (“non omnis moriar”),” said the Latin poet Horace, because “my reputation shall be green and growing.” “More durable than bronze . . . is the monument I have made.” In Marxism, one survives through the society of the future, not as an individual but as a species.

Another one of these palliative remedies, which has been fabricated, is reincarnation. But this is foolishness. Those who profess this doctrine as an integral part of their culture and religion, and thus truly know what incarnation is, know that this is not a remedy or a consolation but a punishment. It is not an extension of life for pleasure but a purification. A soul is reincarnated because it still has something to atone for, and if one must do atonement, then one will have to suffer. The word of God cuts off all these delusive paths of escape: “It is appointed for men to die once, and after that comes judgment” (Heb 9:27). Just once! The doctrine of reincarnation is thus incompatible with the faith of Christians.

Other remedies have appeared in our day. There is an international movement called “transhumanism.” It has many aspects, not all of which are negative, but at its core is the conviction that the human species, thanks to all the progress in technology, is on the path to surpassing itself radically, to the point of living for centuries or perhaps forever! According to one of its most famous representatives, Zoltan Istvan, the final goal will be “to become like God and conquer death.” A Jewish or Christian believer cannot help but immediately think of the identical words at the beginning of human history: “You will not die. You will be like God” (Gen 3:4-5), with the result that we already know.

Death Was Swallowed Up in Victory

There is only one true remedy to death, and we Christians are robbing the world if we do not proclaim it by our words and our lives. Let us hear how the Apostle Paul announces this change to the world:

If many died through one man’s trespass, much more have the grace of God and the free gift in the grace of that one man Jesus Christ abounded for many. If, because of one man’s trespass, death reigned through that one man, much more will those who receive the abundance of grace and the free gift of righteousness reign in life through the one man Jesus Christ. (Rom 5:15-17)

The triumph of Christ over death is described with great lyricism in the First Letter to the Corinthians:

“Death is swallowed up in victory.” “O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?” The sting of death is sin, and the power of sin is the law. But thanks be to God, who gives us the victory through our Lord Jesus Christ. (1 Cor 15:54-57)

The decisive factor occurs at the moment of Christ’s death: “He died for all” (2 Cor 5:15). But what was so decisive at that moment to change the very nature of death? We can think of it visually this way. The Son of God descended into the tomb, like a dark prison, but he came out on the opposite side. He did not turn back to where he had entered, as Lazarus did and then had to die again. No, he opened a breach on the opposite side through which all those who believe in him can follow him.

An ancient Father writes, “He took upon himself the suffering of man, suffering in a body which could suffer, but through the Spirit that cannot die he slew death, which was slaying man.” St. Augustine says, “By his passion our Lord passed from death to life and opened a way for us who believe in his resurrection that we too may pass over from death to life.” Death becomes a passageway, and it is a passageway to what does not pass away! John Chrysostom says it well:

We do indeed die, but we do not continue in it: which is not to die at all. For the tyranny of death, and death indeed, is when he who dies is never more allowed to return to life. But when after dying is living, and that a better life, this is not death, but sleep.

All these ways of explaining the meaning of the death of Christ are true, but they are not the most profound one. This one is found in what Christ, through his death, came to bring to the human condition, more so than what he came to remove from it: it is found in the love of God, not in the sin of human beings. If Jesus suffers and dies a violent death inflicted on him by hate, he does not do it merely to pay an insolvent debt owed by human beings (the debt of 10,000 talents in the parable is forgiven by the king!); he dies by crucifixion so that the suffering and death of human beings would be inhabited by love!

Human beings were condemned to die an absurd death all alone, but entering death they discover that it is now permeated by the love of God. Love could not dispense with death because of human freedom: the love of God cannot eliminate the tragic reality of evil and death by waving a magic wand. His love is constrained to allow suffering and death to have their say. But since love penetrated death and has filled it with the divine presence, love now has the last word.

What Changed about Death

What has then changed about death because of Jesus? Nothing and everything! Nothing in terms of our reason, but everything in terms of faith. The necessity of entering the tomb has not changed, but now there is the possibility of exiting from it. This is what the Orthodox icon of the resurrection illustrates so powerfully, and we can see a modern interpretation of it on the left wall of this Redemptoris Mater Chapel. The Risen One descends into hell and brings Adam and Eve out with him and behind them all those who are clinging to him in the infernal regions of that world.

This explains the believer’s paradoxical attitude in the face of death, which is so similar to that of other people and yet so different. An attitude of sadness, fear, horror, since they know they must go down into the dark abyss, but also an attitude of hope since they know they are able to leave it. “Those saddened by the certainty of dying,” says Preface I for the Dead, are “consoled by the promise of immortality to come.” St. Paul wrote to the faithful in Thessalonica who were mourning the death of some among them,

We would not have you ignorant, brethren, concerning those who are asleep, that you may not grieve as others do who have no hope. For since we believe that Jesus died and rose again, even so, through Jesus, God will bring with him those who have fallen asleep. (1 Thess 4:13-14)

Paul does not ask them not to grieve for those deaths but tells them “not to grieve as others do,” as unbelievers do. Death is not the end of life for the believer but the beginning of real life; it is not a leap into the void but a leap into eternity. It is a birth and a baptism. It is a birth because only then does real life begin, the life that does not lead to death but lasts forever. For this reason the Church does not celebrate the feast of saints on the day of their physical birth but on the day of their birth in heaven, their “dies natalis.” The connection between the earthly life of faith and eternal life is analogous to the connection between the life of an embryo in a mother’s womb and the life of the baby once it is born. Nicholas Cabasilas writes.

It is this world which is in travail with that new inner man which is “created after the likeness of God.” When he has been shaped and formed here he is thus born perfect into that perfect world which grows not old. As nature prepares the foetus, while it is in its dark and fluid life, for that life which is in the light . . . , so likewise it happens to the saints.

Death is also a baptism. That is how Jesus describes his own death: “I have a baptism to be baptized with” (Lk 12:50). St. Paul speaks of baptism as being “buried therefore with him by baptism into death” (Rom 6:4). In ancient times, at the moment of baptism a person was completely immersed in water; all of one’s sins and one’s fallen human nature were buried in the water, and that person came forth a new creature, symbolized by the white robe he or she was wearing. The same thing happens in death: the caterpillar dies, the butterfly is born. God “will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning nor crying nor pain any more, for the former things have passed away” (Rev 21:4). All those things are buried forever.

In various centuries, especially from the seventeenth century onward, one important aspect of Catholic ascesis consisted in the “preparation for death,”[13] that is, in meditation on death and on a visual description of its different stages and its inexorable progression from the periphery of the body to the heart. Almost all the depictions of saints during this period show them with a skull nearby, even Francis of Assisi who had called death “sister.”

One of the tourist attractions in Rome continues to be the Capuchin Crypt on Via Veneto. One cannot deny that all of this can serve as a reminder that is still useful for an age that is as secularized and as unthinking as ours. This is especially true if a person reads the admonition inscribed above one of the skeletons: “What you are now we used to be; what we are now you will be.”

All of this, however, has given someone the pretext of saying that Christianity advances by means of the fear of death. But this is terrible error. Christianity, as we have seen, is not here to increase the fear of death but to remove it; Christ came, says the Letter to the Hebrews, to “deliver all those who through fear of death were subject to lifelong bondage” (Heb 2:15). Christianity does not advance because of the thought of our death but because of the thought of Christ’s death!

For this reason, it is much more effective to meditate on the passion and death of Jesus, rather than meditating on our own death, and we need to say—to give credit to the generations that preceded us—that such a meditation was the daily bread of spirituality during those past centuries.[14] It is a meditation that generates emotion and gratitude, not anxiety; it makes us exclaim, like the Apostle Paul, Christ “loved me and gave himself for me!” (Gal 2:20).

A “pious exercise” that I would like to recommend to everyone during Lent is to pick up a Gospel and read the entire account of the passion, slowly and on your own. It takes less than a half an hour. I knew an intellectual woman who claimed to be an atheist. One day she unexpectedly got the kind of news that leaves people stunned: her sixteen-year-old daughter had a bone tumor. They operated on her. The girl returned from the operating room with an IV drip and all kinds of tubes coming out of her. She was suffering horribly and groaning; she did not want to hear any words of comfort.

Her mother, knowing her daughter to be pious and religious and thinking it would please her, asked her, “Do you want me to read you something from the Gospel?” “Yes, Mamma.” “What do you want me to read?” “Read me the passion.” The mother, who had never read a Gospel, ran to buy one from chaplains; she sat next to her daughter’s bed and began to read. After a while the daughter fell asleep, but the mother continued reading silently in semi-darkness right to the end. “The daughter fell asleep,” she said in the book she wrote after her daughter’s death, “and the mother woke up!” She woke up from her atheism. Reading the passion of Christ had changed her life forever.[15]

Let us end with the simple but powerful prayer from the liturgy, “Adoramus te, Christe, et benedicimus tibi, quia per sanctam tuam redemisti mundum,” We adore you, O Christ, and we bless you, because by your holy cross you have redeemed the world.”