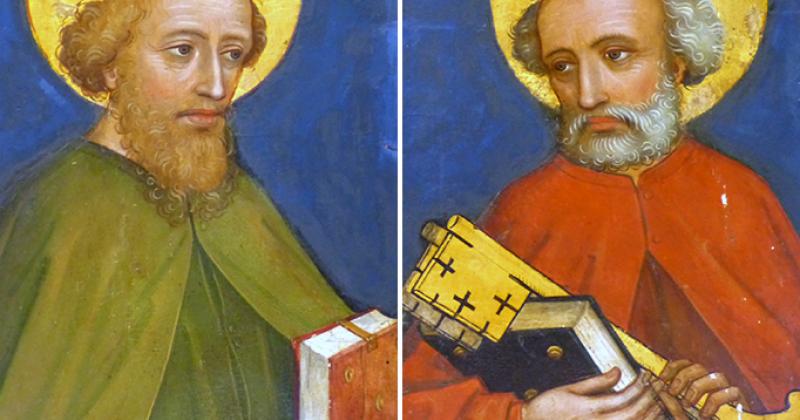

Each in a different way gathered together the one family of Christ. And revered together throughout the world, they share one martyr’s crown.

St. Peter was a fisherman. Fishing nets and tilapia were his daily reality. Born without distinction in a backwater of the Roman Empire, he presumably would have lived and died in total obscurity, had not Our Lord called him to a higher ministry. The green hills of Galilee might have been his entire world.

St. Paul was not a fisherman. He was a man of education and status, who was quite possibly being groomed for an authoritative office or distinguished profession. Some speculate that he may have been a relative of Herod the Great. Whether or not that is true, the New Testament clearly presents him as a Roman citizen, well versed in law and philosophy. He spoke at least three languages (Greek, Hebrew and Latin), and was actively involved in political affairs in Jerusalem at the time of his conversion. We don’t know as much as we might like about his lineage and early life, but the broader picture is reasonably clear. St. Paul was brilliant, and a member of the Jewish elite.

Both of these men were titans. They were the movers and shakers of the Apostolic Age. One was provincial, and the other thoroughly cosmopolitan. One lived his early life in poverty, while the other was born to privilege. On their joint feast day, it’s interesting to reflect on this remarkable pairing. God evidently needed both of these men to establish Christianity in the ancient world. Why was this necessary? What did each bring to the table?

Though St. Peter’s story is in one way quite extraordinary, it illustrates a principle that we see affirmed time and again throughout the Bible: Exaltavit humiles. God delights in exalting the humble, and frustrating the wisdom of the wise.

In the story of salvation, it may happen that a slave’s son is plucked from a river and raised into a great prophet. Shepherd boys may be chosen to slay giants, and a baby in a manger can be the King of Kings.

In the Gospels, St. Peter comes across as an earnest and good-natured simpleton. He is overflowing with zeal, but notably lacking in subtlety or sophistication. Jesus is constantly chiding him after he misunderstands an instruction or blurts out the wrong thing. He tends to need literal explanations for metaphors or parables.

On Good Friday, he fails the critical test by denying Our Lord and running away — but even after he has repented and seen the Resurrected Christ in the flesh, he still doesn’t seem to understand the role that he is meant to play. Instead of making plans for the fledgling Church, he returns to his fishing nets, where Christ must seek him out yet again to ask him to “feed my sheep.” The lesson is repeated three times.

After the Holy Spirit descends at Pentecost, St. Peter changes dramatically. He takes on a new aura of authority. He stops saying awkward things and starts breaking out of prisons, with angels as his assistants. People line the streets hoping that his shadow will pass over them. He’s something of a spiritual superhero. At last, we see the leader that Our Lord presumably saw when he called Simon to be a “fisher of men.” Over time, his simplicity has matured into a purposeful gravitas.

St. Paul’s story is very different. Unlike the other apostles, he doesn’t react with joy the first time he hears the Good News. Rather, his first impulse is to persecute the Church. At no point do we see in St. Paul the wholesome simplicity of an honest fisherman. A dramatic reprimand is needed to set him on the right path.

Despite that, St. Paul became an invaluable asset to the young Church, once his conversion was accomplished. No doubt it was by design that God placed his most scholarly apostle under the authority of a man of lesser birth, but it’s noteworthy that, unlike St. Peter, he didn’t require a lengthy period of growth and development before he was ready for ministry. A relatively brief catechesis was evidently sufficient for him; he was a quick study. Though it took a special divine act to bring him to the truth, his education and pre-conversion experience evidently served as good preparation for his divinely-ordained role.

Obviously, the Pauline epistles are more than just scholarly works; they reflect divine inspiration as well as personal brilliance. Even so, it’s noteworthy that Christians don’t (like Muslims, for instance) view our holiest texts as word-for-word divine speech dictated to a divinely-selected scribe. God could have chosen to drop a pre-written book into St. Peter’s hands, or simply to have Jesus write the New Testament during his earthly life. Instead, he chose a well-educated and scholarly man to write some of the Bible’s most important theological tracts, after Jesus’ Ascension.

St. Paul’s familiarity with ancient (especially Stoic) philosophy and Jewish law is evident in his compositions, and he even specifies in the epistles that God has given him some leeway to insert his personal views. They are inspired, but still very clearly the work of a man.

St. Paul’s political and social savvy are also highly relevant to his ministry. He knows how to exploit his Roman citizenship to win a larger platform, thus extending the reach of the Good News. The Apostles preached the Gospel all across the ancient world, but for the Apostle to the Gentiles, political status and cosmopolitan sensibilities were needed. Saul of Tarsus had these things — and he used them, for God’s ends.

In an age of rising class resentment, it can be difficult to get perspective on the real merits of different classes of people. In America today, the poor and uneducated feel marginalized and unwanted. The rich feel unappreciated and despised. Young and old are increasingly at odds with one another. Every point of conflict is stoked and exploited by our political parties. Forget about building Christ’s Kingdom. How can we even live together?

The Solemnity of Saints Peter and Paul reminds us that God needs our diverse gifts. He needed the strength and simplicity of a Galilean fisherman. He needed the sophistication and brilliance of a Jewish intellectual. From the very earliest days of the Church, the Body of Christ has created communities from people who would never ordinarily have broken bread together. Christ’s call for us to “love one another” is more than just a recipe for communal harmony. It is necessary for us to fulfill the Church’s evangelical mission. Each of us have received valuable gifts. It’s up to us to offer those gifts back to God in service.