Qaraqosh, Tel Kepe, and Karamlesh are just three of the Iraqi towns on the Nineveh plains captured in early August by the Islamic State (IS), but they represent the last major concentration of Aramaic speakers in the world. Pushing northeast of Mosul towards Kurdistan, the jihadist army now occupies the ancient heart of Christian Iraq. According to U.N. officials, roughly 200,000 Christians fled their homes on the Nineveh plains on the night of Aug. 6, justifiably fearful that IS fighters would expel them, kill them, or force them to convert. A local archbishop, Joseph Thomas, described the situation as "catastrophic, a crisis beyond imagination."

Beyond the urgent humanitarian crisis lies a cultural and linguistic emergency of historic proportions. The extinction of a language in its homeland is rarely a natural process, but almost always reflects the pressures, persecutions, and discriminations endured by its speakers. Linguist Ken Hale famously compared the destruction of a language to "dropping a bomb on the Louvre" -- whole patterns of thought, ways of being, and entire systems of knowledge are among what is lost. If the last Aramaic speaker finally passes away two generations from now, the language will not have died of natural causes.

Aramaic covers a wide range of Semitic languages and dialects, all related but often mutually incomprehensible, now mostly extinct or endangered. The last available estimates of the number of Aramaic speakers, from the 1990s, put the population as high as 500,000, of whom close to half were thought to be in Iraq. Today the actual number is likely to be much lower; speakers are scattered across the globe, and fewer and fewer children are speaking the language. Nowhere does Aramaic have official status or protection.

It's a mighty fall for what was once almost a universal language. First spoken over 3,000 years ago by the nomadic Arameans in what is now Syria, Aramaic rose to prominence as the language of the Assyrian empire. It was the English of its time, a lingua franca spoken from India to Egypt. Aramaic outlasted the rise and fall of empires, flourishing under Babylonian power and again under the First Persian Empire in the sixth century B.C.E. Millions used it in trade, diplomacy, and daily life. Even after Alexander the Great imposed Greek on his vast dominions in the fourth century B.C.E., Aramaic continued to spread and spawn new dialects -- for instance in ancient Palestine, where it gradually replaced spoken Hebrew. It was in Aramaic that the original "writing on the wall," at the Feast of King Belshazzar in the Book of Daniel, foretold the fall of Babylon.

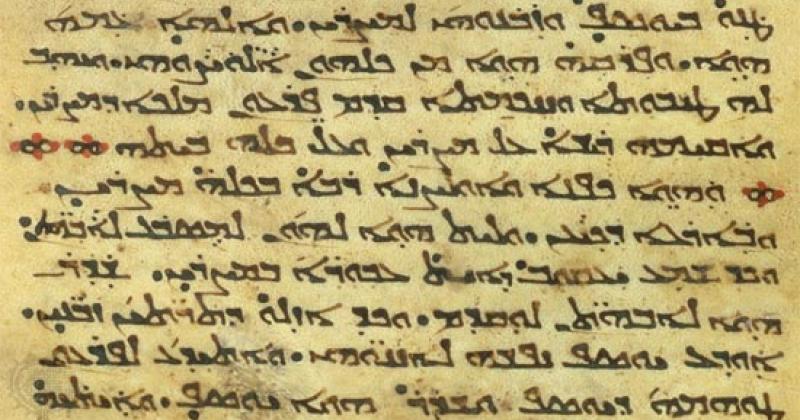

Nearly three millennia of continuous records exist for Aramaic; only Chinese, Hebrew, and Greek have an equally long written legacy. For many religions, Aramaic has had sacred or near-sacred status. It is the presumed mother tongue of Jesus, who is reported in the Gospel of Matthew to have said on the cross: "Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani?" ("My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?") It came to be used in the Jewish Talmud, in the Eastern Christian churches (where it is known as Syriac), and as the ritual and everyday language of the Mandaeans, an ethno-religious minority in Iran and Iraq.

Centuries after Alexander, Aramaic continued to hold its own across much of the eastern Mediterranean and the Middle East. It was only after Arabic began spreading across the region in the seventh century C.E. that Aramaic speakers retreated into isolated mountain communities. The speakers of these varied "Neo-Aramaic" dialects were primarily Jews and Christians in what is now northern Iraq (including Kurdistan), northwestern Iran, and southeastern Turkey. Most Christian Aramaic speakers refer to themselves as Assyrians, Chaldeans, or Arameans; many call their language Sureth.

Though marginalized, this Aramaic-speaking world survived for over a millennium, until the 20th century shattered what remained of it. During World War I, as Ottoman power dissolved, Turkish nationalists not only massacred Armenians and Greeks, but also perpetrated what is known today as the Assyrian Genocide, slaughtering and expelling the Christian Aramaic-speaking population of eastern Turkey. Most survivors fled to Iran and Iraq. A few decades later, facing rising anti-Semitism, most Jewish Aramaic speakers left for Israel. Ayatollah Khomeini's Iran and Saddam Hussein's Iraq added further pressures and persecutions for the Aramaic-speaking Christians who stayed behind. Diaspora became a fact of life for the Assyrians, most of whom now live scattered across the globe, from countries bordering the former Aramaic-speaking zone like Turkey, Jordan, and Russia, to newer communities in places like Michigan, California, and the Chicago suburbs.

Some linguists divide what remains of Neo-Aramaic into four groups: Western, Central, North-Eastern, and Neo-Mandaic. By the end of the 20th century, Central Aramaic was spoken by a tiny community of a few thousand survivors in Turkey. At least in non-ritual contexts, the

"Neo-Mandaic" variety of Neo-Aramaic used by the Mandaeans of Iran and Iraq had dwindled substantially; today just a few hundred people speak it. Meanwhile, Western Neo-Aramaic was down to a single stronghold: the town of Maaloula and two of its neighboring villages, northeast of Damascus. Here a 1996 estimate claimed as many as 15,000 Aramaic speakers, including many children; in 2006, the University of Damascus opened an Aramaic Language Academy, supported by the government of President Bashar al-Assad. There was reason for hope.

But then the Syrian civil war began. In September 2013, Maaloula fell to rebel forces, reportedly a mix of al-Nusra Front (a jihadist offshoot of al Qaeda in Iraq) and Free Syrian Army fighters. The remaining Aramaic speakers fled to Damascus or to Christian villages to the south, according to linguist Werner Arnold, who has worked with the community for several decades. Government forces recaptured Maaloula in April 2014, but "most of the houses were destroyed," says Arnold, and "there was no water supply and no electricity."

A few families returned to Maaloula in July, according to Arnold, but prospects for restoring the academy now seem remote. "I had huge dreams about it," says Imad Reihan, one of the academy's Aramaic teachers, "but in this war, in my country now, I can't think about Aramaic." Reihan has served as a soldier in the Syrian Army for the last four years; he is currently near Damascus. "We lost a lot of it," says Reihan of the language, "and a lot of children don't speak it now. Some try to save the language anywhere they are, but it is not easy." Reihan has cousins in Damascus and Lebanon who are raising their children to speak Aramaic, but dispersal and assimilation can be ineluctable forces. Only in Maaloula will Western Neo-Aramaic survive, says Arnold -- and it remains unclear whether, or when, the community might return.

Thus, until early August, the best hope for Aramaic's survival was in northern Iraq, in the diverse North-Eastern subgroup, with its greater number of speakers and its roots in larger communities. The Christian population of Iraq has been in free fall -- from 1.5 million in 2003 to an estimated 350,000 to 450,000 today -- but the Nineveh plains had been spared the worst. In January, Baghdad even announced its intention to make the region a separate province, a gesture towards Assyrian aspirations for autonomy.

But then in June, IS seized Mosul, as Iraqi forces disintegrated. On Aug. 6, with the Kurdish army withdrawing, IS captured Qaraqosh, Iraq's largest Christian city, with 50,000 inhabitants. The Christian population in the area left overnight, with most fleeing towards Erbil, the Kurdish capital.

Despite U.S. airstrikes in recent days, IS still holds the heartland of Aramaic, now emptied of its original inhabitants. "The threat to the Christian Neo-Aramaic-speaking population of northern Iraq is very great," says linguist Geoffrey Khan, adding that the region has dozens of Aramaic-speaking villages and that "each village has a slightly different dialect." Khan's full-length study of the Neo-Aramaic spoken in Qaraqosh, and similar studies undertaken in neighboring towns, may now stand as monuments rather than descriptions of living communities. "Since each village has a different dialect," says Khan, "if the inhabitants of the villages are uprooted and thrown together in refugee camps or scattered in diaspora communities around the world, the dialects will inevitably die." The unfolding tragedy "is reminiscent of the terrible events in the First World War," adds Khan, which "led to the death of scores of Neo-Aramaic dialects of southeastern Turkey."

Khan's North Eastern Neo-Aramaic Database Project at Cambridge University has compiled data on over 130 of the dialects once spoken across the region, half of which are from Iraq. Most of the others are already gone, or are spoken only by scattered individuals living in the diaspora.

After a century of expulsions and persecutions, can spoken Aramaic survive without its homeland on the Nineveh plains? Between assimilation and dispersion, the challenges of maintaining the language in diaspora will be immense, even if speakers remain in Erbil.

The fate of Jewish Neo-Aramaic, of which several dozen dialects were once spoken across the region, is instructive. Some 150,000 Jews of Kurdish descent, from Aramaic-speaking families, are estimated to live in Israel today, according to author Ariel Sabar's memoir, My Father's Paradise. The survival of the remaining Jewish Neo-Aramaic dialects is "precarious," says Ariel's father, linguist Yona Sabar, "due to the natural assimilation of the Neo-Aramaic speakers into Israeli society and the passing away of the older generation that still spoke and knew Neo-Aramaic from Kurdistan." Several major dialects of Jewish Neo-Aramaic are already extinct, none is thought to have more than 10,000 speakers, and even that high a number seems unlikely, with young speakers now exceedingly rare. "Luckily, the Jews have left these areas [to safety] long ago," says Sabar, one of the foremost chroniclers of how they once spoke.

Unless quickly reversed, the murderous presence of the Islamic State on the Nineveh plains may be the final chapter for Aramaic. Globally, languages and cultures are disappearing at an unprecedented rate -- on average, the last fluent, native speaker of a language dies every three months -- but what's happening with Aramaic is far more unusual and terrifying: the deliberate extinction of a language and culture, unfolding in real time.