Suhila Alshakarji, one of the 12 Syrian refugees that Pope Francis brought with him to Italy from the Island of Llesbos, has lifeless, tired eyes. They only revive when she looks at her daughter Qudus, 7, whose name, she specifies, “means Jerusalem,” playing carefree in the garden and, finally, she smiles.

Not so much time has passed since the little girl — in a rubber dinghy that stopped for almost an hour and a half in the open sea, with 36 other immobile persons to avoid any movement — asked her mother terrorized: “What’s happening?”

“At that moment, I did everything to have her fall asleep, so that if we died, she wouldn’t be aware of anything,” Suhila told ZENIT.

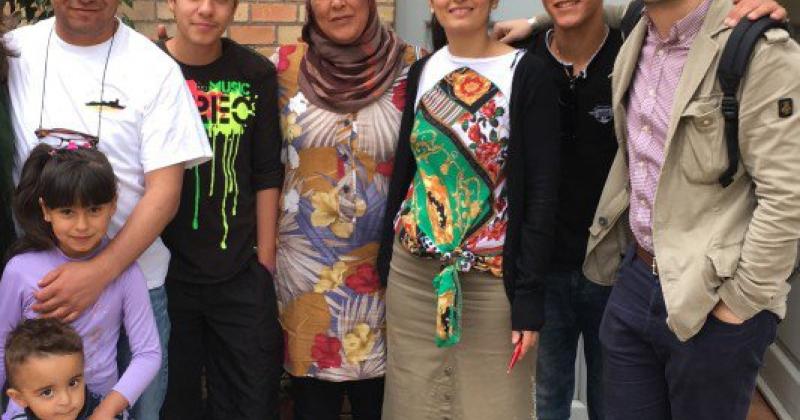

I met with the family, together with the two others brought by the Pope, in the heart of Trastevere, where the Italian School of Language and Culture of Sant’Egidio Community is located, where volunteers are teaching Italian for free to some 1,900 people, between refugees and foreigners.

The drama reported to me by the woman, a former dressmaker not even 50 years old, is only one of the many that the Alshakarji family from Deir Ezzor have had to suffer for some years. Since, that is, those demonic forces of Islamic State, ISIS, Daesh have polluted a territory that up to now was characterized by peace and dialogue.

“We lived serenely in Deir Ezzor for 1,400 years,” said Rami, head of the family, an esteemed teacher before becoming a refugee. In this region known as ‘the Auschwitz of the Armenians, which ISIS has devastated and has also killed 300 civilians, “for thousands of years we have all been equal: Muslims, Catholics, Jews … we had no differences; no one ever asked of what religion you were.”

The Alshakarjis had to flee from there in haste with their children: in addition to Qudus, also Rashid, 18, and Abdalmajid, 15, who in this new phase of life calls himself Totti, like the famous soccer player. “I am happy to have come to Italy, so I have two things: soccer and school. Finally, I can go back to study,” he said, hiding behind a timid smile, while his brother did not proffer a word.

“They are very stressed,” explained the father Rami, who instead is relaxed and affectionate with all the journalists and volunteers of Sant’Egidio that have come to meet him. “They have given interviews every day,” explained Roberto Zuccolini, one of the directors of the Community for relations with the press. “In fact, they asked to be protected from excessive media exposure.”

However, Rami needs to speak; he wanted to give vent to all the evil he had to endure. First of all, his imprisonment by the jihadists, which lasted six months. Rami crossed his wrists to have us understand the condition in which he was constrained to live daily: his hands and feet chained. “They thwarted me and beat me on the back,” he said. “Why,” I asked and naively added: “You are a Muslim …”

“They aren’t Muslims,” he replied almost angered, “they don’t have a religion. They kidnapped and thwarted us only to impose themselves, to make us understand who has the power, to make us afraid.” Rammi’s brother, 55, was also kidnapped for three years; he was also freed later. The same fortune did not touch many of their other relatives. “Three disappeared,” said Suhila, “we don’t know if they are alive. Nine are dead. All the rest of the family is in different cities of Syria, where at present there are battles. Sometimes we heard from them, at others not. We were scared.”

During her husband’s imprisonment, Suhila fled courageously with her children to relatives in Lebanon. She did not think they would ever be reunited. When the miracle happened they decided that the moment had arrived to leave the country. “I decided to leave because I wanted to save my family,” explained her husband. “We fled when we understood the children were risking their life; they are young and could have died from one moment to the next because of the bombings or be forced to enrol” in the jihad.

They know nothing about their home. It will probably be destroyed. “When we left, the village was burnt by bombs.” Impressed in their memory, instead, is all the course endured to leave the country: the flight by night from Deir Ezzor passing through Raqqa, Aleppo and other areas occupied by ISIS, “so dangerous that there even weren’t animals on the road.” “Some left on foot, others hidden in fruit and vegetable trucks,” said Suhila.

“They treated us very badly,” echoed her husband. Every time we met someone who shouted at us. “Stop, who are you? From what area are you? Of what party are you? Of what religion are you?” “Thus, just to disturb us, to terrorize us.”

It all lasted 10 days, then the Alshakarjis arrived at Izmir in Turkey, to try their fortune through the “illegal way,” boarding, that is, a boat returning from Lesbos. “A boat? It was, rathger, a rubber dinghy,” exclaimed Rami.

“We left at 11:00 pm; every 100 meters the motor was blocked. No one died; the sea was inexplicably calm, but at a certain point, in the dead of night, the vessel stopped for 90 minutes. The horizon couldn’t be seen. We called the Coast Guard but it was hard for them to find us. We stayed there immobile: the women and children in the middle and all the men around them. All that was needed was a bit of wind or the least movement and all 36 of us would have ended up in the water.”

Warm again

The terror was replicated for five more hours, until we arrived at Lesbos. The refugees found a completely different scene in the Greek Island. The kids smiled recalling “the impressive welcome: on the beach: There were volunteers, young people and adults, who came into the water to help us come down. Even elderly women helped to push the rubber dinghy to the beach.” Then, once we descended, they threw flowers on us.

The family stayed for 50 days at Lesbos, in the Moria camp visited by the Pope. “We were all right, but we were too many – explained Suhila – basic things were lacking, such as food, water. We didn’t eat well; there wasn’t enough water for a bath; many youngsters and children got sick. Doctors were hard to find.”

However, Suhila added, in the Island the refugees were able to feel that human warmth that they had almost forgotten. “The people were very good, very affectionate,” so much so that little Qudus was immediately at ease. “She went around the camp from 9 am to midnight; she gave a hand to the volunteers to help other refugees.”

My father …

Then Francis arrived: “An angel that came to save us.” To the question about how they received the news that the Pope chose them as one of the three families to bring to Italy, Rami rested his hands on his eyes and answered: “What to say? It was a great surprise, I couldn’t believe it: a personage that we saw on TV and who isn’t even a Muslim had come to take us, to save us … We would never have expected it.”

“We felt a new life inside us, there was hope,” said his wife, managing a smile. And Qudus intervened to tell me: “When I met the Pope I said to him: ‘He is my father, are you also my father?’ I kissed and embraced him and said to him that my name means Jerusalem. He was happy, he joked with me.”

From that meeting with the Pontiff, there was one surprise after another: “We lunched together, we even ate lasagna!” said Rami. Then the arrival in Italy where they met volunteers of Sant’Egidio who welcomed them “as in a family.”

The Community is now offering them food and lodging and teaching them the language. “No sooner they arrived, the family requested political asylum at the Ciampino Airport. They obtained a residency permit,” specified Zuccolini. Now, he added, “they are beginning to integrate. They have done their shopping, they are beginning to look for a school for their children. I was impressed because, although coming from distant places, places of war, in one week they have felt at home. If the will to be integrated exists everything becomes easier.”

At present the Alshakarji family is living “a dream.” They have no prospects: it’s impossible to return home, and to go to another country is difficult. The only hope is that expressed by Suhila heartbrokenly, “All the countries, not only European but also Muslim, should follow the Pope’s gesture and help Syrian families. It’s important because people are dying every day.”

I asked them for a photo to immortalize this very intense moment. The children smiled and said: a “Selfie!” Rami instead, insisted that the photograph be taken in front of the plaque of Sant’Egidio Community: “It’s the least we can do to thank them.”