As a young boy I enjoyed playing Little League baseball. On a couple of occasions, while playing a lesser opponent, our team would be so far ahead that the “mercy rule” took effect, meaning the game would end before all nine innings were played. This was meant to spare the other team embarrassment and to ensure the game ended in a timely manner.

Ordinary mercy involves having compassion and pity on another person. It usually assumes a certain relationship between those who have power and those who are powerless. It is based on the recognition, at some level, of the dignity of those who have less and who are vulnerable. Divine mercy goes even deeper and farther—so deep and far, in fact, that we cannot fully comprehend it. It flows from the heart of Jesus Christ, who not only has pity on us sinners but willingly allowed Himself to be disgraced, beaten, mocked, and killed for our sake.

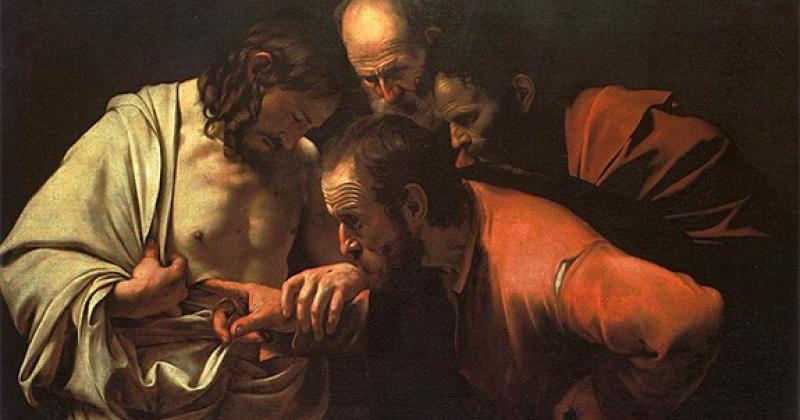

In the language of sports, the crucified Christ was a “loser” so that we might, by His gift and grace, win eternal life. I say “loser” because we know, as today’s Gospel explains, that while Jesus lost His life by giving it up on the Cross, He was restored to life by the Father. Saint Gregory the Great wrote of the doubting Apostle Thomas, “It was not an accident that that particular disciple was not present,” referring to Christ’s first appearance to the frightened disciples in the locked room (Jn 20:19-24). “The divine mercy ordained that a doubting disciple should, by feeling in his Master the wounds of the flesh, heal in us the wounds of unbelief.”

It is tempting, I think, to sometimes look down on the Apostle Thomas, as though we would have readily accepted the witness of the other apostles. Perhaps. But the other disciples, at the first appearance of the risen Lord, also needed to see the hands and side of their Lord. In other words, Thomas asked for the same verification that Christ has given the others. As Saint Gregory indicates, Thomas’s doubt was used by God as a means of mercy for our sake, for the Christian faith is rooted in the historical event of the Resurrection and in the first-hand witness of those who saw, touched, and spoke with the risen Christ.

In April of 2000, Pope John Paul II officially established this second Sunday of Easter as the Sunday of Divine Mercy, recognizing the private revelations given by Jesus to Saint Faustina Kowalska. Saint Faustina saw two rays of light shining from the heart of Christ, which, He explained to her, “represent blood and water.” Reflecting on this vision and Christ’s statement, John Paul II wrote, “Blood and water! We immediately think of the testimony given by the Evangelist John, who, when a solider on Calvary pierced Christ’s side with his spear, sees blood and water flowing from it (cf. Jn 19: 34). Moreover, if the blood recalls the sacrifice of the Cross and the gift of the Eucharist, the water, in Johannine symbolism, represents not only Baptism but also the gift of the Holy Spirit (cf. Jn 3: 5; 4: 14; 7: 37-39).”

The divine mercy, then, involves the sacrificial self-gift that God offers to us, flowing from the heart of the Father, demonstrated in the death of the Son, and given by the power of the Holy Spirit. John Paul II, in his encyclical Dives in Misericordia—“On the Mercy of God” (Nov 30, 1980)—wrote that Christ “makes incarnate and personified [mercy]. He himself, in a certain sense, is mercy.”

In seeing Christ, man sees God and is able to enter into life-giving communion with Him. This beautiful truth is the focus of today’s epistle, written by Saint Peter, which speaks of the great mercy given by the Father through the resurrection of Jesus Christ. Life, of course, is not a game, nor is divine mercy a rule. It is a reality, a gift from the heart of Jesus Christ.