When Karol Wojtyła was born on May 18, 1920, the 1,000-year-old Polish nation had not even celebrated the second birthday of a new Polish state.

He would grow up to live the most distinctive 20th-century life. To all the solemn commemorative dates in Polish history, he added another: June 2, 1979, the date of his triumphant return to Warsaw for his first Polish pilgrimage. That date marked the beginning of the end of the “short” 20th century.

Centuries, as historical periods, are not exactly 100 years long. The late historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote of the “short twentieth century,” from the Great War to 1991, a period dominated by the rise of totalitarian communism and its total defeat. One might mark it 1917-1991, beginning with the Bolshevik Revolution and ending with the dissolution of the Soviet Union.

This short 20th century followed the “long 19th,” from the French Revolution in 1789 to the end of World War I. The French overthrew their monarchy in the revolution, and the Great War brought an end to the royal houses of Russia, Germany and Austria, and dissolved both the Habsburg and Ottoman empires. The age of absolute monarchy was over.

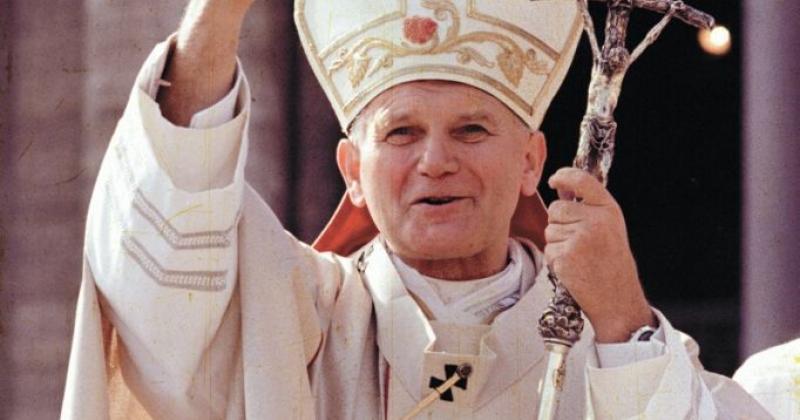

Karol Wojtyła’s 85 years took up the alternatives to the monarchial age, fought against totalitarianism and offered a vision for liberal democracy rooted in the truth about the human person. It was a life that was lived in four successive acts.

The first act was the end of the imperial and monarchial age and what would follow it. That was the world into which Karol Wojtyła was born. In 1918, the state of Poland returned to the map of Europe after more than a century of absence; it had been suppressed and divided up in 1795 by the surrounding empires, Prussia (Germany), Russia and Austria-Hungary.

Kraków belonged to the Austrian crown, and Karol Wojtyła’s father was a soldier in the Habsburg armed forces before 1918. Indeed, in 2004, when St. John Paul II beatified the last Habsburg emperor, Karl (who died in 1922), he remarked that Karl was “my father’s sovereign.”

What would follow the fall of the kings and emperors?

Poland was on the front lines of that question. In 1919-1920, Polish forces engaged Lenin’s Red Army. The totalitarian option for reconstituting Poland arrived in Warsaw before being defeated by Polish forces in what Poles call the “Miracle of the Vistula.”

Would the new Polish state be built on the principles of democracy and constitutional government? Or would it follow the emerging totalitarian options to the east (Soviet communism) and to the west (German national socialism)?

The second act of Wojtyła’s life would begin dramatically in September 1939. Both the Nazis and Soviets would invade Poland and carve it up again, just 20 years after it returned to the map of Europe. Wojtyła arrived in Kraków from his rural hometown of Wadowice in 1938. He would spend the next 40 years until his election as pope in his “beloved Kraków … where every stone and brick is dear to me.” And that entire time he would be fighting the cruelty of twin totalitarianisms, the Nazi occupation during World War II and then Soviet domination after the “peace” of the Cold War came. Poles lament that their country “lost” World War II twice, first in the fighting and second in the peace.

As a clandestine seminarian, a priest and later bishop, Wojtyła would spend his entire adult life contending against the tyranny of the state. Just as the Polish people and their identity had survived from 1795 to 1918 without a Polish state, drawing upon their religious, cultural and historical character, so, too, Wojtyła would combat communism with the weapons of culture, at the heart of which was Poland’s Catholic faith.

The third act of Wojtyła’s life began in 1978, when he was elected Pope John Paul II. For 13 years as the world’s chief pastor he would articulate the fundamental injustice of the Yalta settlement, which consigned Eastern Europe to enslavement in the Soviet empire. His witness was particularly powerful in his native Poland, where his pilgrimages home were an earthquake that brought down the Yalta settlement. His 1979 visit led the year after to the founding of the Solidarity trade union, which quickly became a national resistance movement. Poland was free of communism within 10 years, and it became the first “domino” that would lead to the end of what President Ronald Reagan called the “evil empire.”

John Paul’s third act involved a fulsome defense of human rights, rooting the argument not in Enlightenment political philosophy but in the dignity of the human person, created in the image of God and redeemed in Christ Jesus. This Catholic embrace of human rights built upon the developments of Vatican II and teaching of St. John XXIII, in which the language of human rights was animated by the truth of the Gospel.

After the 1989 tearing down of the Berlin Wall and the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union itself, the fourth act of Wojtyła’s long life began. Having led the defeat of totalitarian communism, he began to propose Christian humanism as the enduring foundation of the free society, a society rooted in the truth about the human person and ordered toward his ultimate good.

Thus began one of the most intense magisterial decades in the history of the papacy. Most papal encyclicals fade in importance as time passes. John Paul published five in one decade that will endure in the decades ahead as foundational documents.

Redemptoris Missio (1990) insisted on the Church’s missionary mandate and addressed what interreligious dialogue should be — a pressing question in the first decades of the 21st century. It clarified that the Church seeks no special privileges, but only proposes the Gospel, which remains good for every people and every culture in every time and every place.

Centesimus Annus (1991) defended the proper use of freedom as the indispensable foundation for a just social order. It remains the great charter of the free society and the antidote to what John Paul’s successor would call the “dictatorship of relativism.” Indeed, in 1991, John Paul warned that a “democracy without values” easily becomes “thinly-disguised totalitarianism.”

Veritatis Splendor (1993) was the first encyclical to address the foundations of moral theology, arguing against the relativism that plagues modernity.

Evangelium Vitae (1995) is the great defense of life against what Pope Francis today calls the “throwaway society.” It remains on its 25th anniversary perhaps John Paul’s signature document.

Ut Unum Sint (1995) committed the Church to ecumenism, with an emphasis on Gospel truth as the solid ground for true human fraternity in a global age.

In 1998, to mark his 20th anniversary as pope, he published Fides et Ratio, on the relationship between faith and reason, defending the possibility of reason knowing the truth and the necessity of faith in order for reason to ask the most fundamental questions of human existence.

And while all this was being done, in 1992, he published the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the papal act with the greatest impact on ordinary Catholic life since the reform of the liturgy by St. Paul VI in 1969.

There was a fifth act in the life of St. John Paul II. From the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000 until his death on the feast of Divine Mercy in 2005, he celebrated the workings of Providence in history and pointed history toward its final consummation, the house of the Father.