Interview with the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch, Aphrem II: martyrdom is not a human sacrifice offered to God in order to obtain his favour. This is why it is blasphemous to call suicide bombers “martyrs”.

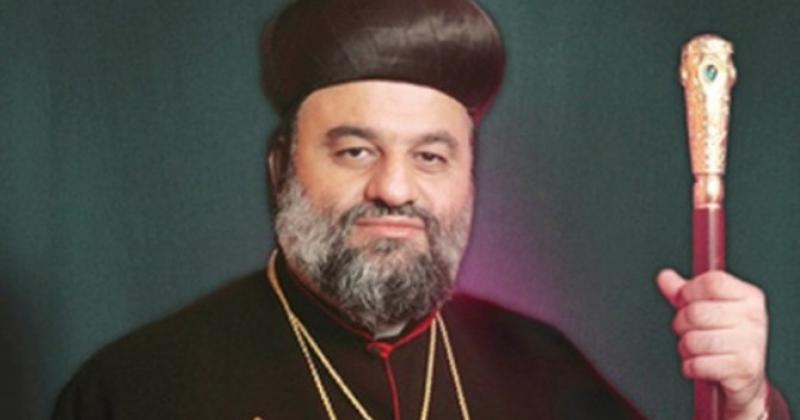

“When we look at martyrs we see that the Church is not just one, holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church. Throughout its journey through history the Church has also been a suffering Church.” According to the Syrian Orthodox Patriarch of Antioch, Moran Mor Ignatius Aphrem II, martyrdom reveals an essential element of the nature of the Church. A connotation that could be added to those professed in the Creed and which always accompanies those who follow in Christ’s footsteps, whatever life throws at them, acting as his disciples. This is a distinctive trait which can be clearly seen now in many of the experiences Christians and Churches in the Middle East are facing.

In recent days, Patriarch Aphrem – who met the Pope in Rome on 19 June – has become involved in the trials and tribulations that are afflicting his people. His last pastoral mission, which has just come to an end, was in Qamishli, his home town. He went there to meet the thousands of new Christian refugees who fled after IS jihadists launched an offensive against the nearby urban centre of Hassake, in the Syria’s north-eastern Jazira province.

Your Holiness, what is the key trait of Christian martyrdom?

“Jesus suffered for no reason, gratuitously. Given that we follow him, the same could happen to us. And when it happens, Christians do not make demands, protesting “against” martyrdom. After all, Jesus promised us that he would never abandon us, he never deprives us of his rescuing grace, as the stories of the early martyrs and today’s martyrs too, attest. They face martyrdom with a joyous expression and peace in their heart. Christ said so himself: blessed are you when they persecute you because of me. Martyrs are not defeated people, they are not discriminated people who need to free themselves from said discrimination. Martyrdom is a mystery of gratuitous love.”

And yet, many continue to talk about martyrdom as an anomaly that should be eradicated, or a social phenomenon that must be denounced and against which we should mobilise and speak out.

“Martyrdom is not a sacrifice offered to God, like those sacrifices which are offered to pagan gods. Christian martyrs do not seek martyrdom to demonstrate their faith. And they do not wilfully shed their blood in order to obtain God’s favour or some other prize, like Paradise. Hence, the most blasphemous thing one can do is to call suicide bombers “martyrs”.

In the West, many keep insisting that something needs to be done for the Christians of the Middle East. Is military intervention needed?

“We are not asking the west for military intervention to defend Christians and all others. We are asking them to stop arming and supporting terrorist groups that are destroying our countries and massacring our people. If they want to help, they should support local governments, which need sufficient armies and forces to maintain security and defend respective populations against attacks. State institutions need to be strengthened and stabilised. Instead, what we see is their forced dismemberment being fuelled from the outside.

Before your recent trip to Europe, you, along with bishops of the Syrian Orthodox Church met President Assad. What did he tell you?

“President Assad urged us to do everything in our hands to prevent Christians from leaving Syria. ‘I know you are suffering,’ he said, ‘but please don’t leave this land, which has been your home for thousands of years, even before Islam came.’ He said that Christians will also be needed when the time comes to rebuild this devastated country.”

Did Assad ask you to deliver some message or other to the Pope?

“He told us to ask the Pope and the Holy See to use their diplomacy and network of contacts to help governments understand what is really going on in Syria. To help them take stock of the real state of things.”

Some Western circles accuse the Christians of the East of submitting to authoritarian regimes.

“We have not submitted ourselves to Assad and the so-called authoritarian governments. We simply recognise legitimate governments. The majority of Syrian citizens support Assad’s government and have always supported it. We recognise legitimate rulers and pray for them, as the New Testament teaches us. We also see that on the other side there is no democratic opposition, only extremist groups. Above all, we see that in the past few years, these groups have been basing their actions on an ideology that comes from the outside, brought here by preachers of hatred who have come from and are backed by Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Egypt. These groups receive arms through Turkey too, as the media have shown us.”

What is the Islamic State really? Is it the real face of Islam or an artificial entity used in power games?

“The Islamic State (Daesh), is certainly not the Islam we learnt about and have lived alongside for hundreds of years. There are forces that fuel it with arms and money because it is useful in what Pope Francis calls the “war fought piecemeal”. But all this also draws on a perverse religious ideology that claims to be inspired by the Quran. And it is able to do so because in Islam there is no authority structure that has the strength to offer an authentic interpretation of the Quran and show authority in rejecting preachers of hatred. Every preacher can give their literal interpretation of single verses too, which appear to justify violence and issue fatwas on the basis of this, without any senior authority contradicting them.”

You mentioned Turkey. Turkish authorities are trying to bring the Syrian Orthodox Patriarchate back. For some centuries it had been moved to a location near Mardin. What will you do?

“Our Patriarchate bears the name of Antioch. When it sprung up, Antioch was part of Syria. It was the capital of Syria at the time. Our ancient churches in Turkey have great historic value for us, but Damascus, Syria’s capital today, is our base now and so it will remain. It is our free choice and no pressure from governments or political parties will make us change our mind. We gave the land that is called Syria its name, a name it has kept. And we are not leaving.”

What effects does the suffering experienced by Christians in the Middle East have on ecumenical relations between different Churches and communities?

“Those who kill Christians do not distinguish between Catholics, Orthodox and Protestants. Pope Francis constantly repeats this when he speaks of ecumenism of the blood. This does not leave things as they are. Living together in such situations brings us together, it leads us to discover the source of our unity. Pastors find themselves as brothers in the same faith and can take important decisions together. For example, it will be important to decide on a common date for the celebration of Easter. In the face of the trials and tribulations of the people of God, which we suffer together, clashes over questions regarding ecclesiastical power prove to be irrelevant.”

What is missing for the achievement of full sacramental communion?

“We need to profess the same faith together and sort out doctrinal and theological issues over which there still appear to be differences. But I must say that Syrian Christians have already made progress in this field because there is an agreement on reciprocal hospitality between Syrian Orthodox Christians and Syrian Catholics. When faithful are not able to participate in the liturgy and receive the sacraments in their own Church, they can participate in liturgies celebrated in the other Church’s places of worship. And they can even participate in the Eucharist too.”

You recently attended a conference organised by the Community of Sant’Egidio in Rome, on the Sayfo, the genocide carried out by the Young Turks against Syrian Christians at the same time the Armenian genocide took place. Why are you so eager to preserve the memory of these painful events?

“In Qamishli, when I was a young boy, I would often go to church an hour before prayer. I would sit among the elderly and listen to their stories. Many of them were Sayfo survivors. They spoke of families that were torn apart, children who were snatched from their families and given TO Muslims. I saw that for them, talking about these terrible experiences was a way for them to get a huge weight off their chests. But for a long time you couldn’t talk about this in public. In recent years, when Churches started to publicly commemorate these tragic events, many people were able to hear stories that had been buried within the family memory as a taboo, something you were not supposed to even mention. For them it was liberating. When we talk about the Sayfo as Churches, our aim is no other than to encourage this inner sense of reconciliation. And our Turkish friends will have to understand this sooner or later: remembering those events is not an excuse for us to stand against them but it can also help them to better understand their past and reconcile themselves with it.”