As the conflict situation in Syria continues to deteriorate and the battle to retake the once predominantly Christian Iraqi city of Mosul from the Islamic State (ISIS) enters its second month, what hope is there for Christians in those countries in 2017?

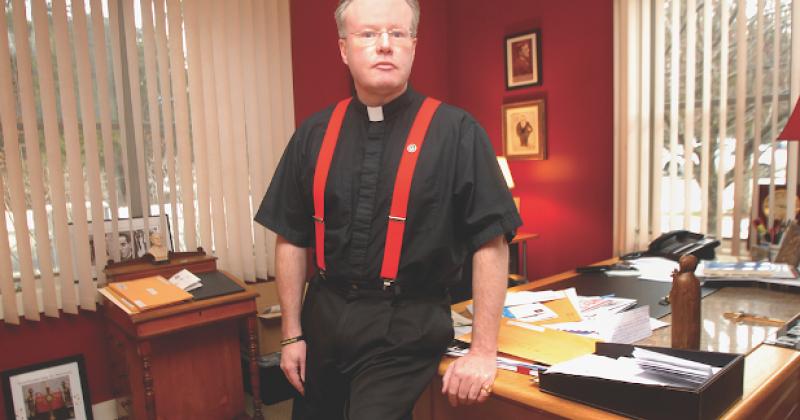

To find out, the Register sat down on December 16 with Fr. Benedict Kiely, founder of the organization Nasarean.org. It is helping Aid to the Church in Need and other charities assisting persecuted Christians in the Middle East. Nasarean.org was behind the creation of objects denoting the Arabic letter meaning “Nazarene” that ISIS daubed on Christian homes to mark them for certain violence and harm. The letter, which Nasarean.org has put on bracelets, lapel pins and zipper hooks, has become a symbol of solidarity with these Christians who have been driven out of their homes.

In this interview, Father Kiely discusses why a genocide declaration continues to be so important for these affected Christians, hopes and fears for the future, and why Islamic extremism is likely to continue even after ISIS is defeated.

What is the current situation regarding the liberation of Mosul and the lives of Christians there?

The current situation, from what I’ve read and heard, and from what people are telling me, is that 80 per cent of the Christians towns are destroyed, the buildings are destroyed; and within the last days, they were driven out. ISIS has destroyed as much as they could. People are going back, and we know that so many of the buildings are booby-trapped. People have gone back and discovered their homes destroyed, and there’s still a great desire to leave. People feel there’s nothing to go back to. They fear there’s no protection. There’s no plan, as we know, for the post-liberation. So the desire for people to leave the country appears to be stronger. It’s not what the hierarchy of the Church wants, which is why there’s a lot of hope with the new Trump administration in America, that America will be more open to assisting them, in terms of emigration.

Carl Anderson, the supreme knight of the Knights of Columbus, has appealed to the Trump administration to protect the Christian victims of genocide. How urgent a task is this?

It is an urgent task, and those two things go together. This is why the genocide declaration is so important: that if the European Union, the British government, the American government have declared these groups, Christians included, are victims of genocide, then you must prioritize victims of genocide, including prioritizing them for immigration. We know the Obama administration was so against any idea of prioritizing, even though their very actions seemed to be of not prioritizing Christians. But if a group has been identified as suffering from genocide, then, obviously, they need special protection and they need special consideration, in terms of their applications for immigration. That seems obvious; it’s not prejudice.

What do you think of those, such as Iraq’s Chaldean Catholic Patriarch Louis Raphaël I Sako, who are trying to encourage Iraqi Christians to remain in the country? Should there be more incentives for them to stay?

There are three things: First, obviously, one totally understands why the patriarchs want people to stay, because they don’t want Christianity being driven from places they’ve been in for 2,000 years. That’s obvious and understandable. But in order for people to stay, they require two major things, which we’ve spoken about: security and jobs. They can’t continue to just stay in camps or in vastly subsidized rental accommodation with no work. So I think it’s now up to some of the agencies, like Aid to the Church in Need and others, like CNEWA (Catholic Near East Welfare Association), to start working on job creation. That’s going to be crucial to keep people there, because they just won’t stay if there’s no work. The charity also will dry up. I’ve heard already that people are very concerned that money is starting to run out. This is the money just to feed and house people at the moment. So, their future in the country depends on jobs and security.

Where will the Christians be in a post-Iraq Iraq?

Many, many people accept the reality that Iraq as such doesn’t exist. There’s going to be a government that’s basically run by Iran. It’s Shiite, and Iraq is basically going to be some kind of Shiite/Sunni state or federation. Where do the Christians and other minorities fit in? Some have this hope that the Nineveh Plain will be an enclave, but, again, several people said to me, “That’s what we would hope for, but who would protect us?” They have perhaps a pipe dream, a pious hope, that America or the U.N. would send troops to protect them. One priest said to me, “We’ll need protection for at least 10 years.” Well, no one is going to do that. So if they can’t be protected, they have no future — it’s as bleak and as simple as that.

After Mosul is fully liberated, could ISIS be a thing of the past in Iraq?

ISIS won’t be a thing of the past in Iraq, it will just germinate into another such group, because we’re not really dealing with ISIS — we’re dealing with Islamic fundamentalism. That’s not going away. These people have a lot of support — it’s a myth that they didn’t have support — and let’s not forget the attacks on Christians are happening from the fall of Saddam, and so this isn’t just ISIS, and it’s not just ISIS in the rest of the world. It’s Islamic fundamentalism — extremism — attacking Christians. They just don’t want Christians around even in relatively peaceful places like Dubai, where Christians are tolerated and go to church. I’ve heard from people there that it’s pretty clear: They don’t really want Christians around. No, ISIS will just have a new name, and like a snake, it’ll just grow a new head. This is the problem. One of the priests in Iraq said to me: “How can we live with the people who’ve betrayed us, our neighbors who stole our houses and betrayed us?” I think it’s pretty unlikely there’ll be many Christians going back to Mosul — the villagers maybe — but Mosul was a hotbed of extremism even before anything like ISIS even existed; attacks were going on. It’s not hopeless — there are lots of things we can do to help them, but that point of security and jobs is key.

There’s a fundamental lack of trust.

There is zero trust; there’s no trust in the government in Baghdad, there’s no trust, really, in the Kurdish government, and there’s no trust between neighbors. It has been betrayed. And as people have said, if this has happened to us before, and not just this time, of course, because we know the history and had been abandoned by the army before, what’s going to stop that happening again? The army said they would protect them from ISIS and ran away.

They could do that again?

Easily. Looking to Syria, that’s quite a different case, but Christians are also suffering there. Christians, as we know, are made up of 10 per cent of the population of Syria. But, again, the bishops and patriarchs are begging for people to stay, but Syria is so fluid, with this tremendous war going on. President Assad is seen, because he’s a member of a religious minority, in some sense, as a better hope for Christians than the alternative, which is basically, again, Islamic fundamentalism. There’s very little reality to talk of “the rebels” — the rebels are all pretty much fundamentalists of some kind or another.

Which you don’t hear about in the West?

No, you don’t hear anything about it in the West; they just talk about “the rebels.” Every Syrian Christian I’ve met, while accepting that President Assad and the regime is far from good, say this is the only protection they have, and they’re very fearful of what the alternative is. It’s rather like an Iraqi priest said to me about living under Saddam, “There’s bad and there’s worse. Which would you rather live under? You’d rather live under bad.” So I’m sure, for the Syrian Christians, as well [that’s true]. It’s far from perfect living under the Assad regime, but the alternative is much worse.

When the Iraq war was being debated in 2002/2003, I remember interviewing a close friend of Pope St. John Paul II, who said John Paul was against the war not just because he was against war, but because of what would happen to the Christians there. He foresaw what would happen. If Assad goes as well, are you likely to get the same hounding of Christians?

You’re looking at the expulsion, really, from the cradle of Christianity, and I’m always struck [by] what [Melkite Catholic] Archbishop [Jean-Clément] Jeanbart of Aleppo said to me nearly two years ago, which was, when you read that passage on Pentecost Sunday: “That’s us. We are the Church of Pentecost; we were born on Pentecost Sunday.” To think of that Church — far more ancient than any of us in the United States — being destroyed, that ancient heritage is beyond tragic. So we must support in any way we can, in prayer and charity, the works of the agencies that are trying to help Christians. It disappears from the news cycle, but it can’t disappear from the life of the Church in the West, in America. People think: “Oh, the Christians and Mosul: The area has been liberated, and Christians can go back, and it’s all over.” This is not ending in our lifetime. This is a lifetime’s work to retain and protect Christians in the Middle East, and it’s the responsibility of every committed Christian to care about their brothers and sisters in the faith. St. Paul says in his Letter to the Galatians [6:10]: Do good to all men, but first to those of the faith. So we have no alternative.

What is your charity currently working on?

Nasarean.org is a charity, and we’re continuing to support Aid to the Church in Need and also continuing to support our own projects, specifically trying to create jobs. We’re helping to pay the salaries of 10 women in a village in northern Iraq, a place which actually means “Eden” in Aramaic. These women have sewing machines, and they’re making products; they’ve also bought a bakery. So that’s precisely what we’re trying to do: to give them jobs, so they cannot just have handouts, but make a life again.