In a new teaching letter titled Placuit Deo, the Vatican’s Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith (CDF) attempts to address the underlying difficulties that prevent people from embracing Church teaching regarding the universality and uniqueness of Christian salvation.

One of only three official documents emerging from the Vatican’s doctrinal office during the pontificate of Pope Francis, and the first under the current prefect, Archbishop Luis Ladaria, S.J., the 3,300-word text bears the unmistakable stamp of the Francis pontificate.

In keeping with the Francis style, the document is not so much doctrinal as pastoral, in that it deals not with the idea of the unity and universality of salvation in Christ-which it takes as a given-but rather with the underlying psychological and social causes of why contemporary men and women find this teaching to be difficult to understand or accept.

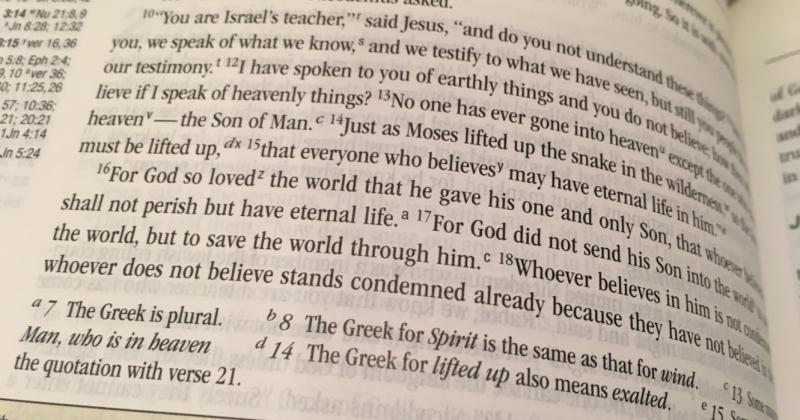

The Christian faith “proclaims Jesus as the only Savior of the whole human person and of all humanity,” the text states, which is difficult for the contemporary world to understand, in particular because of the twin errors of individualism and subjectivism that are prevalent in the modern mentality.

In writing about the theology of salvation (soteriology), the prefect of the CDF, Archbishop Luis Ladaria, finds himself firmly in his wheelhouse as an expert in Christology as well as theological anthropology. In 2007, he wrote Jesucristo, salvación de todos (Jesus Christ, the Salvation of All), a 180-page book examining the universality of salvation in Christ.

In the year 2000, the CDF published its declaration Dominus Iesus on the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church, which was, in many respects, an extended theological explanation of Saint Peter’s lapidary statement: “Salvation is found in no one else, for there is no other name under heaven given to mankind by which we must be saved” (Acts 4:12). It was also a reaction to intellectual trends relating to a theology of pluralism that sought to find paths to salvation in different religious traditions.

In the press conference introducing the Declaration, then-Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger noted that the text was a response to the ever more popular idea “that all religions are for their followers equally valid paths of salvation,” a notion that contradicts core Christian belief regarding the universality of Christ’s salvific mission.

Less than a year after Dominus Iesus, the CDF published a notification on the book Toward a Christian Theology of Religious Pluralism by Father Jacques Dupuis, S.J. lamenting “notable ambiguities and difficulties on important doctrinal points, which could lead a reader to erroneous or harmful opinions.”

More specifically, these points “concerned the interpretation of the sole and universal salvific mediation of Christ, the unicity and completeness of Christ’s revelation, the universal salvific action of the Holy Spirit, the orientation of all people to the Church, and the value and significance of the salvific function of other religions.”

While Placuit Deo addresses “Certain Aspects of Christian Salvation,” little ink is spilled on the core questions tackled by Dominus Iesus, and the new text rather attempts to explain its reception (or lack thereof) “with particular reference to the teachings of Pope Francis.”

The two errors assailing soteriology today, the letter proposes, are those of an individualism “centered on the autonomous subject” that smacks of the age-old heresy of Pelagianism and a subjectivist spiritualism reminiscent of the Gnosticism of the first centuries of the Christian era.

The first error attributes exaggerated importance to human effort, as if self-reliance and rugged individualism were sufficient to work out one’s personal salvation. The second error spiritualizes human liberty apart from the reality of other people and one’s own bodily existence, as if a person were not a part of physical creation.

While the first error is fairly easy to understand, the second may require closer analysis.

In explaining neo-Gnosticism, the letter states that “a merely interior vision of salvation is becoming common, a vision which, marked by a strong personal conviction or feeling of being united to God, does not take into account the need to accept, heal and renew our relationships with others and with the created world.”

In other words, a subjective feeling of closeness to God seems to be replacing the objective conditions of the moral order, and the mere conviction that one is okay substitutes the necessary requirements that goodness entails.

This neo-Gnosticism “presumes to liberate the human person from the body and from the material universe, in which traces of the provident hand of the Creator are no longer found, but only a reality deprived of meaning, foreign to the fundamental identity of the person, and easily manipulated by the interests of man.”

The created order is not “a limitation on the absolute freedom of the human spirit” because true salvation includes the “sanctification” of the body itself, it states.

This text relates closely to previous teachings of Francis, particularly in reference to what he has called “gender ideology.”

In Amoris Laetitia, his 2016 teaching letter on marriage and the family, Francis criticized gender theory for its denial of “the difference and reciprocity in nature of a man and a woman,” and for its dream of “a society without sexual differences.”

“An appreciation of our body as male or female,” he said, is “necessary for our own self-awareness in an encounter with others different from ourselves.” Efforts to cancel out sexual differences based in anatomy are a symptom of a society that “no longer knows how to deal with it,” he wrote.

Earlier still, in his 2015 encyclical letter Laudato Si, Francis wrote that “thinking that we enjoy absolute power over our own bodies turns, often subtly, into thinking that we enjoy absolute power over creation. Learning to accept our body, to care for it and to respect its fullest meaning, is an essential element of any genuine human ecology.”

How could we experience the salvation mediated by the Incarnation of Jesus, Placuit Deo asks, “if the only thing that mattered were liberating the inner reality of the human person from the limits of the body and the material, as described by the neo-Gnostic vision?”

Overcoming neo-Pelagianism requires acknowledging “the absolute primacy of the gratuitous acts of God” and thus “humility is essential to respond to his salvific love and is required to receive the gifts of God, prior to all of our works.”

Overcoming neo-Gnosticism, on the other hand, requires acknowledging the goodness of creation-including the human body-as it comes forth from the hand of God, and allowing Him “to renew our actions, so that, conformed to Christ, we are able to fulfill the good works that God has prepared in advance, that we should live in them.”

It also requires going beyond ourselves, to “touch the flesh of Jesus, especially in our poorest and most suffering brothers and sisters.”

It would seem that in Ladaria, Francis has found a collaborator who understands the pastoral tone he is trying to convey, while building on the doctrinal foundations laid before him.