Following is the reflection by Most Rev. Archbishop Pierbattista Pizzaballa, Apostolic Administrator of the Latin Patriarchate of Jerusalem, for the 15th Sunday of Ordinary Time, Year C, July 14, 2019:

There are two expressions that give us a first key to understanding today’s Gospel passage (Lk 10:25-37).

The first we find immediately at the beginning, when the evangelist Luke says that a doctor of the Law stands up to test Jesus.

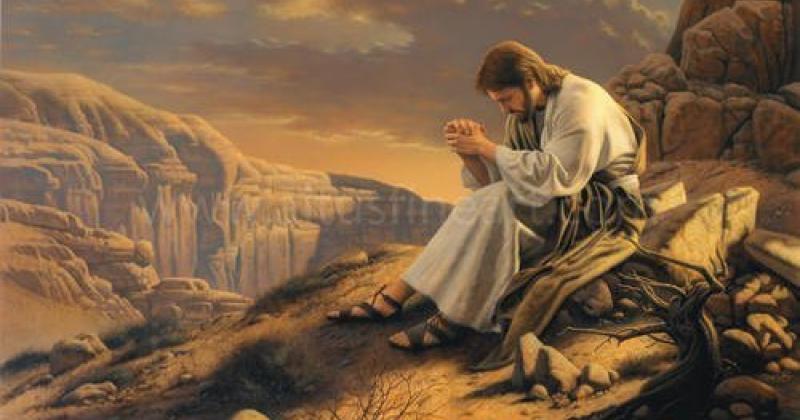

This is the same verb that Luke uses in Chapter 4, where Jesus, in the desert, is tempted by the devil (Lk 4:2). It is a strong expression and tells us that, hidden behind and within the words of the doctor of the Law, a temptation is hidden, or the proposition of a false image of God.

We find the second expression in verse 29, when the doctor of the Law, after Jesus’ words about his question on what is necessary to do to inherit eternal life, wanting to “justify himself”, puts another question, about who is one’s neighbor (But because he wished to justify himself, he said to Jesus, “And who is my neighbor?”).

The doctor of the Law, therefore, first tempts Jesus, and then justifies himself. But what’s at stake? What is the temptation and from what must he justify himself?

Behind the questions of this teacher there is the great temptation of religious persons, that of closing God within the confines of one’s human reasoning, of possessing Him, of making Him in one’s own image: a clean God, predictable, distant, who does not enter into life, who does not inhabit history. With the risk of making him become an ideology, which in the end justifies only its own selfishness.

Our character, in short, goes to Jesus seeking to define what love is and who he needs to love, hoping that these cases will mark some boundaries in which he also can be safe without too many unexpected events, from which he does not have to leave, that will spare him the effort of dying and being born again. He seeks an answer that will give him the certainty of being right, of getting out of it “justified”.

Jesus avoids entering the logic of the teacher of the Law and does not answer. To the first question “What must I do to inherit eternal life? (v. 25), He invites him to answer himself, He refers it to him, to seek for himself in the Law of which he is a teacher. To the second question “Who is my neighbor?” (v. 29), He tells a parable that is not an answer, and which concludes with a further question. Jesus does not leave him deceived and does not leave us in our deception.

This is the context in which the parable of the “Good Samaritan” arises (Lk 10:30-35).

The victim, fallen into the hands of brigands, is seen (Lk 10:31,32,33) by three different persons. The priest and the Levite see him. The text uses two prepositions – antì-parà (Greek) – that indicate a “moving around,” and make it clear that the priest and the Levite turn away, they wander around him, in other words they avoid him and continue their journey.

We dwell only on the gestures of the Samaritan, who, unlike the first two characters, not only sees but also has compassion (Lk 10:33): before physically crossing the street, he has already made room in himself for the man, and not in the name of belonging to the same religious affiliation, nor of some political harmony, but in the name of uniquely belonging to the same humanity, to the same needy fragility.

Compassion causes him to make the step that the “faith” of other two characters had not caused them to do. The Samaritan, however, has the ability and the freedom to cross over, to depart from the rigidity of those confines that would prevent different worlds coming into contact.

He makes a liturgy of human, sacred gestures that bow over the man just as in the temple one would bow down before God. He makes his offertory with oil and wine, he uses what he has, and then does not leave it at that. He does not decide he has done enough; he goes all the way. If he takes it on, he entrusts it to another, involving him in his story of compassion. And then he pulls out two coins, pays the person assuring that he will come back.

After this parable, Jesus gives back to the teacher of the Law the questions about the neighbor but gives it back to him inverted. (Which of these three, in your opinion, was neighbor to the robbers’ victim? v.36): there where he would have liked to define the boundaries and decide who is inside and who is outside, who we must love and who not, Jesus invites us to do the opposite, to eliminate the boundaries, to become ourselves neighbors of whoever comes our way, without choosing.

Only by eliminating these boundaries do we discover the real face of God, freed from the temptation that we can love and serve Him, without serving the brother who happens to be near us.

+ Pierbattista