When the Pope visited Bethlehem, in the West Bank, last month, he was less than 100 km (60 miles) away from Gaza. But for the 4,000 Christians in this crowded Palestinian territory along the Mediterranean Sea , he might as well have been on the moon. Like nearly all Gazans, they are barred from leaving the Gaza Strip by Israeli restrictions. An Israeli embargo on supplying many essential goods to them has left the impoverished area unable to repair buildings destroyed or damaged by an Israeli offensive. Added to all that, the tiny Christian minority has been living since June 2007 under the Islamist rule of Hamas. Faced with conditions like that, attending a papal Mass is a luxury few would even dream of.

Behind the altar at Holy Family Church in Gaza, paintings depict Gospel scenes that all took place within a few hours’ drive. There’s the Nativity in Bethlehem, Jesus’s baptism in the Jordan River and the Last Supper in Jerusalem — all places that the pope visited. But the only place the Gazan Catholic faithful at Sunday Mass here could hope to visit anytime soon would be the route of the Flight to Egypt. Joseph and Mary would probably have brought Jesus through the Gaza region while fleeing Herod’s plan to kill all newborn boys in Bethlehem. The rest are all unreachable for them.

I made a quick visit to the Christian community in Gaza on Sunday to gauge the mood following the pope’s visit to Israel and the West Bank. My colleague and I had only a few hours until the border closed in mid-afternoon, so there was only enough time for some impressions and short conversations at the Catholic and Greek Orthodox churches and with a Hamas government minister.

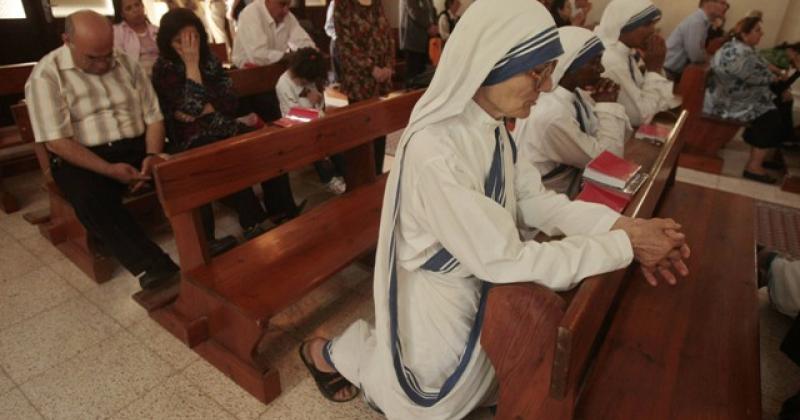

There were about 70-80 Catholics attending Mass when we arrived at Holy Family Church in the old city centre of Gaza. After Mass, several parishioners talked about the pope and about life in the isolated territory. “For us, his visit didn’t mean anything,” Salama Saba, a 60-year-old unemployed electrical engineer, said when we asked about the pope. “He should come here to Gaza to see the destruction My son was killed. My home was destroyed. There is nothing for us.”

Rami Tarazi, an unemployed 31-year-old, said he would have loved to go see the pope, but it was not possible to get a permit to leave Gaza for Bethlehem. “You had to be over 40 to qualify, and then they only chose some people. We don’t know who did the choosing.” Several people said only about 90 of Gaza’s 4,000 Christians were allowed to leave to go see the Pope.

Life under Hamas is a delicate topic. “We don’t have any problem with them,” Saba said carefully. A 21-year-old student, who asked not to be named, said Hamas didn’t do anything specific against Christians but didn’t protect them when they came under attack from Islamist extremists. Over at the Greek Orthodox Church of Saint Porphyrous, a parishioner there who also asked not to be named said Christians were concerned about Hamas although he gave no details.

Husam Al-Taweel, a Christian member of the Palestinian Legislative Council elected with Hamas support, gave a fuller view of the situation for Christians in Gaza. “I won’t say there are no problems and we are living in heaven,” he said in an office at the Greek Orthodox church, where he is secretary general of the board. “But there is no discrimination against Christians in particular. We don’t see ourselves as a minority, but as part of the Arab majority.”

Taweel said 90 per cent of Gaza’s 4,000 Christians were Greek Orthodox, the rest being Roman Catholic and a few Baptists. The Christian community has dwindled because of migration, he said, but added: “This is not a problem only for Christians. This is a problem for the Palestinian community in general. They’re all looking for a job, a better future.”

The rise to power of Hamas had not changed life much for Christians, he said. “Nobody asks my sister to put on a veil,” he said, “I will not allow anyone to interfere in my life as a Christian.” But there had been attacks on Christians, such as some who sold liquor or on a YMCA library, and the culprits were never found. One man, Rami Ayyad, was abducted and killed, apparently as a result of his work at the Protestant Holy Bible Society. Taweel spoke at length about the need to apply Palestinian law, implying that this wasn’t done equally.

Asked about sales of alcohol, which is no longer available in Gaza, Taweel said drink was a luxury that Gazans couldn’t even think of anymore. “We can’t even find clean water. Even bottled mineral water here has to be boiled before you can drink it — although you usually don’t have enough gas, and if you use electricity, the power is often cut off. So alcohol is a luxury we don’t expect to find here anyway.”

With only a short time left, we paid a quick visit to Dr. Basem Naim, minister of health in the Hamas government in Gaza. With his fluent English and German, Naim often meets foreign journalists to explain Hamas policy. When I asked what had changed in terms of religion since Hamas took over in Gaza from Fatah, the rival, secular Palestinian party that still governs in the West Bank. He started by saying that Hamas, for all its Islamist agenda, was first and foremost a Palestinian resistance movement and it saw Christians as part of Palestinian society. If there were tensions between Muslims and Christians now, he said, they were more due to efforts by evangelical Christians to convert Muslims than any policy of Hamas. He said evangelical Christians with U.S. support had been working among Palestinians for the past 15 years.

According to Naim, several leaders of established churches in Gaza had asked the government to ban this missionary activity.

“If we stop these people, there are many in Europe and the United States who are just waiting for such a move to start talking about Hamas as a religious regime,” he said. But Hamas was primarily a political organisation, he insisted. “We have not decided yet about the final model of Palestinian society,” he said.

“We cannot impose things by force.”

Naim presented Hamas as being in “the middle ground” in the Islamic world. “What is allowed here would be banned in Saudi Arabia,” he said, citing the right for women to drive as an example. “There are extremists to the right of us, who cannot understand that Christians can come here and talk about Christianity. But they are not only against Christians. They would also be against Muslims who shake hands with a lady. They could attack a wedding party if they’re playing music. They could attack internet cafes because people can see sex films there.”

Short though the visit was, I got the impression that Hamas had much bigger problems on its hands right now than to start Islamising what is already a traditional Muslim society. The police arrest people for possessing drugs, but not alcohol, which is simply confiscated, residents said. It was never especially common, even before Hamas took over. Women wear headscarves, but beards are not noticeably more frequent than in other Arab societies. Other residents said what was most noticeable since Hamas took over was a kind of self-censorship that people practiced themselves. There were probably more women wearing headscarves and young men were more careful about playing loudly secular music in their cars.

On the way out, we saw one scene that showed it was still an Islamist administration. Hamas border guards searching the bags of two women aid workers driving into Gaza were in the process of confiscating a bottle of white wine they’d found in one suitcase and were searching elsewhere in their car for more.