Behind the scenes - between lights and shadows - of the renunciation of Patriarch Laham. An emblematic story of the “inner” malaise that crosses many Christian Middle Eastern communities. Potential candidates to succession and the - spiritual and pastoral - emergencies that they will have to face

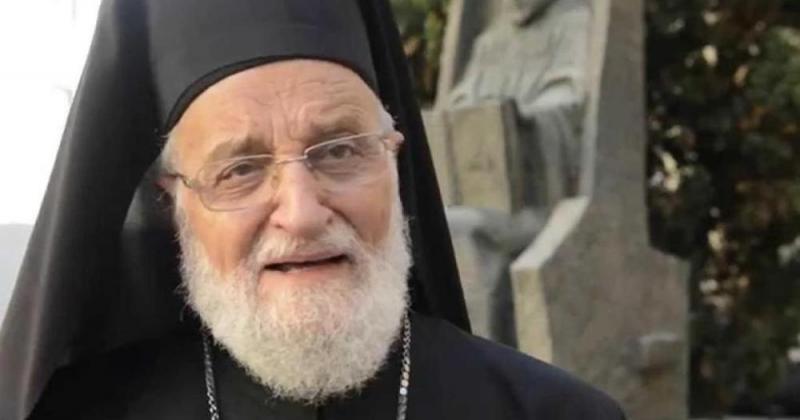

In the end, Patriarch Gregory III Laham pulled out. He is no longer the Primate of the Greek-Melkite Catholic Church. His somewhat troubled exit ultimately confirming his impulsive attitude. It also reveals factors - often removed - of the “inner” malaise that today crosses many Christian Middle Eastern communities.

Patriarch vs. Synod

On Saturday May 6, the Vatican Press issued Pope Francis’ letter in which he informs Gregory III of having accepted the Patriarch’s renunciation of the patriarchal assignment, a request submitted to Pope Bergoglio by the Patriarch at a recent hearing. In the letter, Francis considers the Patriarch of Antioch’s decision as opportune and necessary “for the good of the Greco-Melkite Church.” In the papal letter it is intentionally stated that the renunciation of the 85-years-old Patriarch has taken place “spontaneously”, and includes many customary thanks to Gregoire called a “zealous servant of the People of God”, “for keeping the attention of the international community focused on the tragedy of Syria”

Actually, the resignation of the Patriarch is the outcome of the clash developed in recent years between the Patriarch and an ever-widening majority of Melkite Bishops. According to local sources, it was the Melkite synod to pressure the Patriarch into signing the letter of renunciation on February 23. However, at the time the Patriarch had given the impression he wanted to freeze the process triggered by his signature. According to an official statement issued by the Patriarchate in early March, Gregory III would have remained in office, and was actually preparing to launch new projects.”

The “Church of Islam”

Gregory III has always been little accustomed to ecclesial prudence. When he was Vicar of Jerusalem, and his name was Loufti Laham, his pro-Palestinian intervention (he also recently joined the hunger strike of Palestinian prisoners in Israeli prisons) and criticisms of Western military interventions against Saddam’s Iraq Hussein aroused considerable discussion. “We are the Church of Islam,” he would say, baffling theorists of an alleged clash between the “Christian” West and the Muslim Ummah. Elected Patriarch in 2000, he remarked, as a Christian born in Syria, that “Islam is our environment, the context in which we live and with which we are historically supportive”, to the extent that “When I hear a verse of the Koran, for me it is not something strange, it is an expression of the civilization to which I belong. In his view, “After September 11, there is a plot to eliminate all the Christian minorities from the Arabic world” as “Our simple existence ruins the equations whereby Arabs can’t be other than Moslems, and Christians but be westerners.”

Ever since the Syrian conflict broke out, Gregory III has been suspicious of the “Arab Spring” matrix, proposing himself as a leader of the highest Christian hierarchs more in accordance with the scenario-interpretation proposed by the Syrian regime. As early as summer 2012, he denounced an ongoing campaign against bishops and Patriarchs of the Syrian Churches, accused by several parts of submission and connivance towards the regime. “The freedom of the shepherds,” Gregory said at that time “was guaranteed everywhere and it still is up to today, both in their behavior and in their public and private statements ... We will not allow anyone to speak on our behalf or on behalf of Christians in Syria, to manipulate our statements or to charge us with accusation of any kind.” With the same strength, he then went on supporting reconciliation initiatives such as those sponsored by the inter-confessional movement Mussalaha, which insurgents saw as facade operations in support of the regime.

The roots of the crisis

The disagreement between the retired Patriarch and much of the Melkite Synod did not emerge from political issues. Even the most disapproving Melkite bishop almost fully share the Patriarch’s geo-political reading of the Syrian tragedy. And among those bishops, no one believes Assad can be excluded from negotiations on the future of Syria. The root of the clash between the Patriarch and Melkite Bishops lies in Gregory’s management of the Church, which many considered autocratic, as he would take decisions without confronting with anyone and without taking account of the synod dynamics. There is also criticism on the lack of transparency in the allocation of funds received and collected around the world in favor of local communities overwhelmed by the war. Further, it is known that many priests have abandoned Syria during the war. As the Patriarch in official speeches urged everyone to stay in the country, in several cases, he also provided support to emigrant priests. Especially – and with shared reasons - if they were married priests who would expatriate to protect their families and prevent their children from compulsory enrollment in the army.

The paralysis of the Synod, which lasted for at least two years, had a negative impact on the lives of many Melkite communities scattered in the Middle East, and left several dioceses - such as the Archbishopric of Petra and Philadelphia, Jordan - without a bishop.

What will happen after Gregory?

Many Melkite bishops were eagerly awaiting the resignation of Patriarch Laham, but did not seem to be equally concordant with the choice of his successor. During the vacancy, Jean Clément Jeanbart, Aleppo’s Melkhite Bishop, who will convene the Synod for the new Patriarch within two months, will administer the Melkite Church. Potential candidates to the Patriarchy of Antioch are several: among them, Jeanbart himself, Damascus Vicar Joseph Absi and the 78-year-old Cyril Salim Bustros, Melkite Archbishop of Beirut and Jbeil. The new Patriarch, whoever he is, will face the suffering and discomfort conditions of the Christian communities in the Middle East, which the media usually fails to record. Spiritual and pastoral emergencies that cannot be solved with electoral campaigns and fundraising organized by some Western agencies.