I’m certain of this: if we all were to pray the Lenten prayer of the great St. Ephrem the Syrian, Father and Doctor of the Church, we would bring about the coming Kingdom of Heaven with great speed.

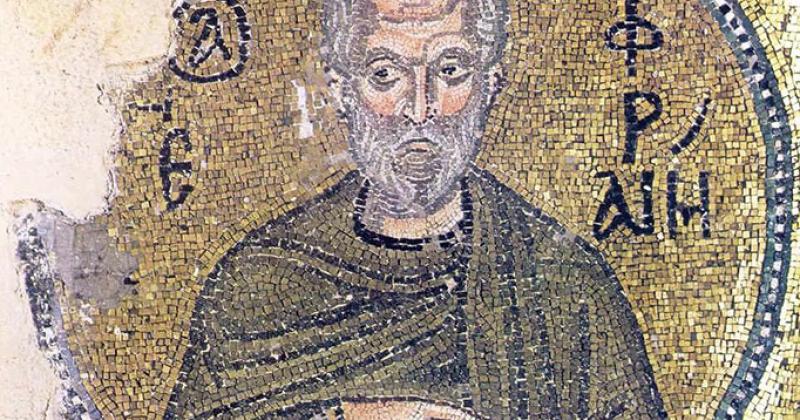

He was a culture warrior who by some accounts ended life as hermit. He was a prolific apologist who also composed memorable hymns. He is a revered figure in the Eastern Churches, and one of the very early Doctors of the Church as named by Pope Benedict XV in 1920.

Yet St. Ephrem the Syrian, who died in A.D. 373, is largely an unsung hero among Catholics of our time. Even so, he is fast becoming a favorite of mine, given that we both share in common being a deacon and church musician.

In fact, I first heard of St. Ephrem because a liturgical musician I knew years ago had “Ephrem” as her middle name (yes, “her”). She had been born on his feast day, June 9, and her mother had the intuition that the example and intercession of this great saint would loom large in her daughter’s life. And it was so—a lifelong love of music enveloped her, inspired by the astonishing story of a saint dubbed the “Harp of the Holy Spirit.”

A classic account of St. Ephrem’s life and brief synopsis of his literary work can be found here. My imagination is captured by accounts of his stalwart defense of the faith in the face of secular and gnostic heresies that would inspire his immense corpus of poetry and prose. We often think that contemporary culture is unique in its struggles against the spirit of the age, and perhaps every age has its unique moments, but life in the early Church was clearly a daily struggle of often-monumental proportions.

St. Ephrem and his fellow Christians from Nisibis, for example, had to abandon their home city in the face of persecution and resettle in Edessa. Even in the aftermath of this, Ephrem steadfastly preached the fullness of the faith he had embraced early in life, despite apparently having had a father who was a pagan priest.

Part of the reason St. Ephrem is underappreciated is because it’s not exactly easy to render ancient Syriac hymns (and even prose) in English that carries the same poetic value as the original. Additionally, the rhythm, cadence, and melodies of his hymns have been largely lost to the ages.

Nonetheless, it is well worth the time and energy to take a look at the work of this venerable Church Father and Doctor, who rightly belongs to both East and West, given that he lived and wrote so long before the unfortunate division of Orthodox and Catholic took place. He is truly a universal treasure for us all.

One of the most popular of St. Ephrem’s prayers still in use today is a Lenten prayer widely employed today by Eastern and Orthodox communities. Here is one English version of the text:

O Lord and Master of my life! Take from me the spirit of sloth, faint-heartedness, lust of power, and idle talk. But give rather the spirit of chastity, humility, patience, and love to Thy servant. Yea, O Lord and King! Grant me to see my own errors and not to judge my brother; For Thou art blessed unto ages of ages. Amen.

This incisively brief prayer is remarkably jam-packed with relevance for a believer seeking ever-greater purification and enlightenment during the penitential and holy season of continuing conversion. “Master of my life” isn’t quite the language of the warm-fuzzy, me-centered liturgy that has sadly permeated some of our current prayer and thought. It sets the stage for the humbly offered petitions that follow.

Whole chapters could be written on our struggles to even want to grow in the virtue of humility, and here in one sentence is a plea to God to strip us entirely of the chief vices that still plague the believer as much now as they must have in Ephrem’s time. And there is a real, visceral quality to naming these vices as “spirits”—we’re not dealing solely with our struggles with interior human weakness, but we are each engaging in a lifelong spiritual battle to shun all the temptations of the world, the flesh, and the devil.

Countering these spiritual enemies are the great virtues that we may petition the “Master of our lives” to grant us, through His great grace. Chastity, humility, patience, and love may be ours already in some measure, but a true penitent seeking Christian perfection will know that, just as every breath we take is a gift from God, every moment we spend in our earthly existence is an inestimable treasure of time that can yield for the devoted disciple even greater growth in holiness, in preparation for our ultimate encounter with our Lord and King.

But the spiritual battle frequently leaves us too easily distracted from such noble requests. While we can only change ourselves, and not others, that fact alone can drive us to avoid the interior work we need and instead lament at how terrible are the sins of so many others around us whose failings seem overtly manifest.

And yet the truth is this—we must say “yes” to the work required to sanctify our own souls. If we do not, we are lost. What are we waiting for? If we owe it to others to point out flaws such that they may attain heaven more readily, do we not first owe that same debt to ourselves?

I’m certain of this: if we all were to pray the Lenten prayer of the great St. Ephrem the Syrian, Father and Doctor of the Church, we would bring about the coming Kingdom of Heaven with great speed.

And with even greater love.

Give it a try—pray St. Ephrem’s prayer and then pray in gratitude for his example and in supplication for his intercession. Let yourself be enveloped in the music of the “Harp of the Holy Spirit.”